In the first two instalments of this family story, I left off around 1920 with Idris and Annie meeting and marrying and the same for Fred and Rose. In this next section I’ll take us through from 1920 to 1950, when these two families come together. There will be a few deviations into the period before to build up more background on the central characters.

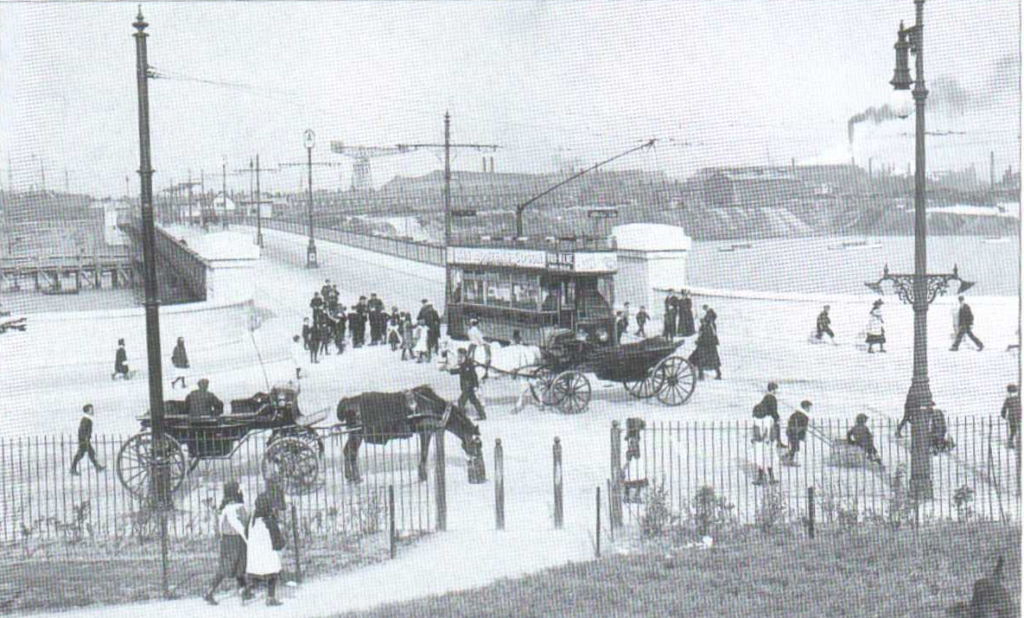

By this time men had just got the vote and women of over the age of thirty too, but there is still some way to go in improving democracy. In America, the Ford Motor Company has been going for 17 years, producing ‘affordable’ cars, but there are very few here (see picture of Barrow in 1923 below). Indeed, milk and coal was still often delivered by horse and cart and there were few cars on the streets, even of London, when I was young, beyond the end of this period.

During the 1920’s there were financial slumps and a General Strike. From the end of the 1920’s till the outbreak of the Second World War there was The Great Depression. Then there was the war itself and then, finally, some glimmers of hope at the end of the 1940’s. What a time to bringing up a (large) family.

Many of the tales in this part of the story come from my Dad, who had been born in 1919, my aunt Vi, who was born the same year and my mum, born in 1924.

Bridgefoot 1920-1939

Let’s start a bit before our current start date. In the previous story I repeated the family tale of Thomas William Bowness going back to America to sell property there. While I was trying to research this, I mistakenly concluded that it may have been a myth and that the family only rented the Dukes Head pub in Bridgefoot. With some further digging I have come up with a sequence of events where Thomas owns 1 property on ‘Peel Street’, then another cottage as well and then owns ‘The Dukes’ and two cottages, over a period of three years. The tale may be true. Sadly, soon after, Thomas dies and by 1921 his wife Elizabeth is owning those properties, and living in and running the pub. She lived until she was 83 in 1944, only the year before her son Herbert died in 1945. Herbert had returned to Australia and the younger son George Bowness is living at the Dukes too but working in the local mine.

At the same time the newly married Idris and Annie Morgan are living in Workington and my aunty Vi was born there in 1919 presumably in a rented house. At some point before my mum is born in 1924, the Morgans move into the cottage attached to the pub called Ellers View. Idris never owns a house in his life, as the cottage is owned first by his mother-in-law, then by his wife and later by his two surviving daughters and finally by Violet, who buys the other half from my mum.

Bridgefoot and Little Clifton are often viewed as the same place, which is not surprising, as there have only been around 480 people living in both together for more than a hundred years. There are two rivers, the Lostrigg and the Marron, that join and then feed into the Derwent shortly after. It says something about the family and the Welsh exodus to this part of the country that there were 9 Morgans born here in 1921 alone. From 1919 to 1924, Idris and Annie had four children, but Elizabeth Varty Morgan only lived for three months and young Annie died when she was 12 in 1935. Violet was the first and my mum Hazel was the last, so 5 years younger than Vi. Imagine the effect of those two deaths on Violet and one later on Hazel.

I’m going to take a detour back into the life of Idris before marriage. We’ll come back to Annie later. Idris was 36 when he married and had already been working for around 24 years, so was probably fairly set in his ways. The implications of this have just hit me in relation to a tale from my mum about him playing Rugby for Workington and the players in the scrum sticking their fingers up noses and other underhand practices. My guess is that he would have been late teens and early twenties when he played. Like all those working men players, he would have been tough as old boots. He was also relatively tall for the time at around 1.73m. When you sit in the north of England and talk about Rugby, you must check which code first, League or Union. I always assumed that Idris chose Union because of his Welsh family background. It turns out that there was no choice. Rugby League was not set up in that area till 1945. When you look at the number of Welsh who set up home round Workington, it is tempting to connect this concentration on Rugby Union with that influx, but the game was still only developing in Wales too at this time. The Zebras, as Workington RFU are known, were founded in 1877 and briefly split from the RFU to play semi-professional rugby at the time Idris would have been playing. They were quite successful, but the finances were dodgy and they later folded and managed to sneak back into the RFU by taking over Workington Trades RUFC. Whatever the facts of the history, it is possible that Idris was part of a relatively successful rugby side and he may even have earned some extra money from that.

Like so many people in these industrial areas, Idris did not get drawn into the First World War, because of where he worked. Not taking part in a war is not always straightforward, as Jingoism often paints nonparticipants in a bad light. I suspect that this may have been a factor in him joining the Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes in 1916. The main purpose of this vaguely Masonic organisation at this time seems to have been to raise funds for ambulances to be sent to the front.

In the first part of the story, I mentioned that Idris and Annie might have met in the Dukes Head. In fact, for several years the families lived near each other in Workington, to the south and east of Vulcan Park. The reason I assumed the pub was that Idris certainly drank quite a lot throughout his life. He said that being poor stopped him becoming an alcoholic, but the amount he drank also helped him to stay poor. The women in the family were quite right to control the finances as much as they could. Though I never new him as a drunk, I suspect my mum’s dislike of drinking came as a response to her dad. She never wanted to lose control and I think that she will have witnessed Idris losing control. He must have felt that he had done well to move straight from his mum and dad’s house at the age of 36 to live, a few years later, in a little cottage, provided by someone else, and attached by a yard and two back doors to the local pub. One household duty was to go next door with a jug to get a supply of beer for him. Idris also smoked a pipe all the time throughout his life and the pub was also the source for the pipe bowls, as he would swap a new bowl for one that was already seasoned by another customer. In a very small house with an equally small cooking range in the main room, the addition of Idris smoking would have made for a thick atmosphere, so I suspect that he was an early case of being sent outside to smoke.

Idris and Me about 1962

With that bit of background about Idris, it is worth comparing it with Annie. She was 25 when they married. She had been born in America and brought up with her grandmother living in the same house. Grandma and father came from a family of farmers, cartwrights, blacksmiths and other trades, who would probably consider themselves a little above Idris’s family, whatever the reality. Her mother had been in service in Carlisle and Canterbury Cathedrals, so probably had a similar view of status. By the time they were married Annie’s family owned several properties. Annie herself was a dressmaker, which was considered a respectable occupation. In addition, whether they practiced or not everyone in Annie’s background was Church of England and Idris’s family were Chapel. Such small differences of background matter and I suspect they would have influenced Violet and Hazel. Both churches existed in the village at the time, though the Wesleyan Methodist chapel later became a private dwelling, and that despite having rented seating as a source of income. The CE church is higher up the hill of course.

The irony of that implicit snobbery, that was visible even during my lifetme, is that the Morgans seem actually to have been literate from way back and that literacy was likely due to the Chapel backgound.

So by 1925 we have Idris and Annie, Violet, Annie junior and Hazel in the little cottage between the pub and the farm entrance. There is an outside toilet in the yard, together with a coal store. There are two bedrooms upstairs, a small main room and a similarly small kitchen/washroom and larder. Baths would have been in a tin bath in front of the range in the main room, or in the washroom. Washing was hung out in the pub yard.

A cooking range as I remember it.

Idris works long hours int the Steel Works at Moss bay, the other side of Workington, so will also have spent some time travelling to and from work. Annie will have been at home with the children all the time, though Vi would have been at school by now. The Chapel had built a school, but I am not sure whether this was the one they attended. I remember going with Idris up to an allotment towards what is now the A66 across the Lostrigg and up School Lane (Cat Bank) and now I type that, I seem to remember there was a very small (no more than a house really) school up there, which would make sense, and I think that was the one they attended. I don’t know whether the allotment was a recent thing after Idris retired, but I can imagine him disappearing up to one from the start and fresh vegetables would have been welcome in both the house and in the pub. For a town person, he seems to have fitted well into country village life, going for long walks, tickling trout in the rivers, putting growing tree limbs under steady strain so that they developed a pre-bent handle for a walking stick and similar activities.

When I was young, I remember someone wading into a deep pool with a baling hook on the end of a pole to catch a very big salmon, that was later shared round the village, via the pub. I don’t suppose that was a new activity to the area. The little Mill race to the farm was fed from a weir further up the Marron that also made a salmon ladder, so those deep pools had seen lots of big salmon in their time.

Annie’s recipe book gives good evidence of both the times and her varied background, with recipes for Canadian Beans, German Cake, potato scones, potato pastry, American doughnuts, bottled fruits, risotto, Italian cutlets, cowslip wine, the use of campden tablets, salad cream, mushroom catsup, green tomato chutney, how to have fresh runner beans in winter (no fridges remember), non-slip floor polish, cough mixture, mildew stain remover, embroidery ink, woodworm killer, whooping cough mixture, Indian chutney, Phosferine (considered a miracle cure for nervous ailments), Zambuck (origin obscure but a patented balm beloved by rugby players), dandelion wine and so on. Members of the family could go out along the hedgerows and into the fields to collect hazelnuts, wild fruit, mushrooms and other goodies and between Annie and Elizabeth they could be turned into tasty and nutritious fare.

This brings us back to general history again. The Herberts in the early parts of this story still lived and worked on ancient strip farming plots. They could carry out crafts, such as making carts, blacksmithing and joinery while still living on plots of land where they could keep animals and grow food. As time went on agriculture grew in scale, squeezing the margins of those who worked the land and so workers moved into bigger industrial areas. The larger these areas were the further people got from the ability to feed themselves flexibly. Bridgefoot seems to have been a reasonably sized place for this mixed rural and industrial life.

Good as the place was for growing up, it was still hard. Elizabeth now ran the pub on her own, so had to hire staff. Annie may have helped occasionally but I suspect that Idris did not really help with childcare. I do not think he would have been trusted with the pub either. The family were still poor and in 1929 there was not enough money to send Vi to the Grammar School in Cockermouth. This was very common at that time. Children would pass to go to the Grammar School, but the families could not afford the uniforms, books, sports kit, food costs and bus fares involved. The same probably applied to Annie junior. In the National and Board schools pupils who didn’t go to grammar school were kept on till they left. In 1918 the age at which they could leave was raised to 14. In These schools, the teaching was often very limited. Brighter pupils could reach the end of what the teachers could teach and helped with the younger pupils. A further example of how poor people in general were then was my mum’s tale of going to pick her single Christmas present long before Christmas and then saving her pocket money to pay for it. Of course some of that is not just lack of money but also a life lesson on how to value things.

In 1933 Vi will have left school. I am not sure what she did straight after school but by 1939 she was down in Westmorland working at the Meathop Sanatorium as a probationer nurse, which is a first year training nurse. Here they specialised in TB at this time. I remember her telling me tales of walking across the train viaduct over the river Kent to go out in Arnside. Such behaviour was probably not approved of. At this time nurses were usually expected not to marry and most who did left soon after. As the working hours were typically around 60 per week it would be hard to balance that with life as a mother. This was pre the NHS and nursing was not really regulated. The Second world war would start the regulation process.

Being called a Probationer in 1939 indicates that she may have worked for several years as an auxiliary nurse before being accepted on to basic nurse training. The war brought more regulation to nurse training and probably a minimum entry age of 18. Trained nurses were divided into Registered nurses and Enrolled Nurses as well the lower level Auxiliary nurses. The combination of a lack of school leaving certificate, changing rules and Vi’s age may well have pigeon-holed her into the enrolled nurse category.

Cockermouth Grammar School

Vi moving away, and Annie junior dying at the age of 12 in 1935 would have eased family finances and Hazel was allowed to go to the Grammar School in Cockermouth. Here she was taught violin, became a proficient High Jumper and matriculated, which was the certificate showing you had completed education to age 14 or 15 and passed in at least six subjects and obtained a credit in at least five including maths, English, science and a language. Hazel was listed as still at school in the 1939 register at the beginning of the Second World War. Interestingly there were two children, Annie and William, called Smith registered as living at Ellers View as well.

I recently had a very strange experience after visiting Bridgefoot with a friend and chatting to some local artists about the area. We followed that visit with a trip to Cockermouth and included popping into a well known tool and other hardware store with an ancient equipment and tool museum at the back. While browsing I noticed some old school photos that turned out to be from the period around the start of the second world war. My mum was surprisingly easy to spot.

After school Hazel went to work in the offices at the Steel Works and remained there until she was 18. Pressure for new nurses had been great at the start of the war and only grew. Women were being effectively conscripted into war roles and in nursing this route led to being an enrolled nurse, which had a shorter two-year training period. Hazel realised that she was able to apply for full registered nurse training. She did so and went to train down in Barrow-in-Furness in 1943. Before we see what happened there let’s step back a bit and look at Fred and Rose Scott, who we left there in part two of our story.

Barrow-in-Furness 1918-1939

Fred and Rose’s children are shown here in this extract from the Family Bible.

At first they lived at 44 Monk Street and at some point International Man of Mystery Samuel Scott gave them the wherewithal to purchase 140 Schneider Road. He put money in trust so that Joseph could only get the interest, the capital remaining for his offspring. Each month he would go to the Solicitor to pick up his interest, then spend it in the pub. I think it was in the Monk Street house that Joseph Scott came to live with them. As far as I can tell these houses are small three-bedroom terraced houses with an internal bathroom nowadays, though the indoor facilities may have been added later, with a toilet at the bottom of the yard originally. The yard is very small and the front door opens straight onto the street. Fred and Rose had one bedroom, the girls another and one end of the biggest bedroom was walled off to make a fourth bedroom for Joseph, with the boys sharing a bed (sleeping top to tail) in the other half. If any of the girls moved out when they left school at 14, it may have eased conditions. Dad told a tale that Joseph believed they were trying to poison him to get at the trust fund, so he used to make dad taste all the food first. Joseph died in 1933 and that may have been what triggered the move to Schneider Road. These were newer houses on the coast road with a much better sense of space.

Below is the view from the house now.

However, the view I remember was slightly different. There was a high banking on the other side of the road and behind it was one of two large reservoirs. Beyond that was scrub and then 100 years’ worth of slag heap covering the whole horizon. On the plus side the firework like scenes from the hot waste pouring down the side were spectacular and there was often a horse tethered on the banking eating the grass. The adaptation below might give you the feel.

It is worth saying a word or two about Joseph and Samuel, though it is all hearsay. In later life Joseph was no longer a choirboy. He had become careless with his money and drank too much. Like most men in those days, he either expected a wife to look after him, or in the absence of one, a daughter, the wife of a son. I think this is the reason for Samuel looking after Joseph’s children financially.

As far as I know, several of the family passed to go to the Grammar School, but there were always too many children to be able to afford to send any of them, like Vi in Bridgefoot, they just stayed on in the same school and helped teach the others. Unlike the tales I have written about Ulster farms and barefoot children, here in Barrow the roads were often more solid and dad told me that they wore clogs with ‘corkers’ on the bottom.

It was not just the number of children that made money tight. The financial problems throughout the 20’s and 30’s meant that companies kept trying to get more for less out of workers, changing piecework rates and arrangements, what counted as working time and other aggravations for the workers. The result was often industrial action. Even if you didn’t want to take part in the industrial action, the companies might just lock everyone out of the site and refuse to pay them. The heavy industries like coal and steel and industries like shipbuilding, that were in temporary decline because of the post war slump in demand, were the hardest hit by the conditions. Churchill’s insistence on the gold standard protected the rich at the expense of exports failing.

These things certainly affected the Scotts. Fred was locked out several times and my father was very bitter about his mother having to go to the Board of Guardians for relief. This was the latest adaptation of the Poor Laws, set up in the sixteenth century. There you were made to explain yourself and how you had managed to get into this state, to the well-off citizens of the town who made up the board. They could then decide if you would receive relief and how much you would get. Dad would be horrified if anyone suggested he had anything but a well-fed childhood, but anyone looking at his bowlegs and hearing how much weight he put on in the army, would have to assume there was shortage of food for the youngest children. Fully grown dad was 1.7m tall, which is about average for the time, so he was fed enough overall, but I suspect it varied as times got hard. Fred was a traditionalist who used his belt to punish the children and I suspect expected to take priority in the feeding line. As he was only around 1.59m tall that may not have used up huge amounts of food. Other tales dad told give clues in the same direction. He used to get a penny pocket money and rushed out to use it to buy a ‘penny bag a floppers’ (bruised fruit). He also said that he used to be sent out to buy his mum fish and chips and would be given a taste as a reward. However, Fred was not like his father and drank very little. Family resources were generally well managed. By the late 1920’s Fred had been working for the same, large, powerful company for around 25 years. He had already worked on the submarines that have been the main reason the shipyard has been kept alive in Barrow until the present day. It is clear that individual family decisions are not blame for the relative hardship.

Gradually each of the children grew up and started work, each one easing the financial situation. Dora married George Doughty in 1934 and they moved into a house not far from and not dissimilar to the Schneider Road house. Ruth (Ruby) and Blanche married the same year. Blanche moved with George Livesey to another house near Schneider Road. Ruby Bartlett seems to disappear, and I can’t remember the family tale about that. Her first daughter Marilyn is born in 1938 in Barrow and Ruby Deborah (Della) is also born in Barrow in 1945, which is where I remember Ruby living with her husband George (Judd) Bartlett. Fred C 2 went to work in the Co-op as a grocer (he could still roll sugar into a sheet of paper when he visited Beamish museum many years later) and disappears before the 1939 register is compiled, which suggest he was already in the forces.

As well as wearing an over-the-top uniform at some point, Albert (Ally) plays football and breaks his collar bone twice, disobeys his father and goes to work in the shipyard, but realises he has made a mistake, so some family influence gets him a job as an apprentice joiner and he worked on building the Ormsgill Housing Estate. Walter Gilbert (Gilly) trains as a Joiner/Fitter too.

Barrow 1939 – London and Beyond 1950

The second world war came along when Fred junior was 21, Ally 20 and Gilly 15, so, as they were not in protected organisations, the older two went into service and Gilly was able to put that off for part of the war at least. It took me years to figure out why my dad had so many stories about places he had served, and they were mainly around the UK. Finally, I twigged that the war did not go well for the Allies at first, so troops came back from the continent, if they had got there in the first place, and they went round this country building fortifications, setting up defensive gun emplacements and training other troops. The Barrow lads suddenly got to know a whole lot of other places in the UK.

While they were still in the UK, Fred was at one camp and went into the local town for a bit of social life. When he came back the camp sentry shouted ‘Halt, who goes there’ and raised his rifle. As they were all in plain sight and knew each other, Fred replied, ‘It’s me you silly bugger’ and stepped forward, at which point the sentry pointed his rifle at the ground and fired, not allowing for the ricochet of the bullet and detritus from the ground. The result was that Fred was off to the hospital, then sent home to convalesce and afterwards put on light duties, which meant into the kitchens and peeling lots of potatoes. On his next visit home to Barrow, Fred talked to his mum, and she taught him how to cook and they wrote down recipes for several meals scaled up for the numbers involved. Rose was of course used to large scale catering so knew the problems, tricks and solutions. Apparently, it was successful and after a while the officers got wind of the quality of the meals being served to the men and transferred Fred into their mess.

Meanwhile Ally had become an Engineer and learnt to build bridges and destroy them, find landmines and disable them, lay landmines, build sea defences, build entrenchments, and many other similar activities. If you have never thought about the role of army engineers, they are often among the first to go forward, to lay a path for others to follow, and they are often among the last to retreat, to set blockages to enemy advances. While the troops were stuck in this country, he travelled around from place to place either laying defences or demonstrating some of the activities. I think one of the places he visited was Bessbrook in Northern Ireland, which is a quaker village near the border with the Irish Republic. As the Republic was neutral in the war, this made the border between north and south a potentially hostile one, so the engineers would have been helping set up defences. Dad told us that, as there was no pub in the village, the train would slow down before it approached the village and passengers would jump off, run into the local pub, pick up a pint that was already pulled, throw down their coins, quaff the pint and run back to the train. Looking at the history it is possible that this was the Newry Bessbrook tramway, which went under the Craigmore Viaduct and carried more local traffic than the Belfast Dublin line that crossed the viaduct itself.

Everywhere you went with dad in later years, he would either say ‘I was stationed there’ or ‘I built an exhibition there’ (one of his post war jobs). When you consider that the war started in 1939 and it was not until 1944 that the big European land push back started with the D-Day landings, there was plenty of time to move around the country preparing for invasion. This meant that both he and Fred were able to get leave back home to Barrow reasonably frequently. Fred’s future wife, Vera Low, was originally from Pickering, so presumably Fred met her when stationed nearby. Dad’s future wife had conveniently moved to Barrow, so either he met her when on leave, or after the war when he returned.

I will cover more about Mum and Dad in a separate section later, but for the moment a bit about the next piece of travel. Once the Allies had set foot on the continent again, Ally was involved in Sapper activities for real. He was clearing land mines, swimming across rivers with ropes in the middle of the night, as the first stage of building a bridge across, building pontoon bridges, setting up defences and a whole host of other activities. When I find it and re-type it, I will put up a short story I wrote about one tale, but briefly he described walking across a field in pitch dark to get to where they had a task to do, they could hear other people moving around on the other side of a hedge but had no idea what side they were and anyway had to concentrate on their mission. At one point he trod on something that was obviously human, but which made no noise. He didn’t know whether the person was dead or alive, nor which side again. The person didn’t shoot or stab dad, so he had to ignore it and carry on. That pretty much describes the chaos of war.

Research has shown that, throughout history, most soldiers have done anything they can to avoid killing anyone else in person. This involves shooting high, pretending to have a jammed gun, anything to avoid the deed. Politicians, a jingoistic press and public and high-ranking officers have done anything in their power to force people to fight, or to insulate them from the emotional effects of what they are doing. Most wars would end much quicker if it was left to ordinary soldiers. Dad never liked responsibility throughout his life and feared failure. As a result, he refused all promotions and turned down the chance to learn to drive army vehicles. He just kept his head down and got on with the job. He was proud that he carried a Bren Gun throughout the war but never shot it in battle. He was the opposite of proud of laying landmines, with their indiscriminate effects.

The other thing that affected Dad deeply he didn’t talk about much and that was the things that the Germans had done to their own people, such as the concentration camps and the starvation of the general populace. It must have been a terrible emotional trauma to witness these things and, understandably, dad could never sit back and look at these things in a wider context to spread some of the blame.

VE Day in Barrow. Note the lack of men.

While Fred and Ally had been moving round Britain and the continent, life had gone on back in Barrow, apart from a brief period in April and May 1941 when German Bombers reached it and targeted the shipyard and steel works. Probably because of the distance involved, the town was badly prepared for the raids and so suffered a high casualty rate. Future head of MI5, Stella Rimmington had ironically been moved to Barrow from London for the duration of the war for safety and later described her experiences of the bombings. Housewife Nella Last also described her experiences, as part of a war-time data collection project and these were later dramatized starring Victoria Wood as ‘Housewife 49’.

On the family front Dora and George Doughty had already had a child (Sylvia) before the war in 1936. They had another (Glennis) in 1943. Ruby and Judd Bartlett had one daughter (Marilyn in 1938, but the next (Ruby Deborah or Della) was born in 1946. Blanche and George Livesey had one Daughter (Mavis) in 1940, but the next (Gillian) was not born until 1948. Fred (jr), Ally and Gilbert settled back into Barrow post-war life for the next 3 or four years. After the war the heavy industries of Iron, Steel and shipbuilding had already started to decline. Ally worked on rebuilding some of Barrow and then on building the power station at Winscale (later Sellafield). Fred went to work in the offices in the shipyard. I am not clear what Gillie was doing at this point.

I’m not sure when exactly Ally meets Hazel but it would almost certainly have been at a dance. Dad didn’t go to the pubs like many of his contemporaries, but took himself to dances instead. They obviously hit it off and Ally proposes to Hazel in the pantry of Ellers View and then they tell the family. My dad also remembers Grandma seving behind the bar in the pub and said she was a really cheerful person. Again I’m not sure what the arrangements about the pub and other properties were after great grandma’s death. Presumably that had happened before dad went up there.

In a mirroring of earlier family events a bit of an exodus suddenly starts after the war ends. Blanche and George move down to London and Gillian (Gilly) is born there in 1948. Word spreads across the family and plans are made for more of them to move down there. Ally has met up with Hazel and they are planning to marry. Hazel has started training as a midwife and completes the first part of her training down in Bolton at the beginning of 1949. Ally gets annoyed at the John Lewis Partnership, who he is working for up on the Winscale Power Station. They want to move him to another part of the country, but not London, where he has requested to move. He ‘hands his cards in’ (resigns), leaves employment straight away and comes down to stay with Blanche and starts work on a building site. He is amazed when they ask him which bit of housebuilding carpentry he specialises in. He is used to just doing all of it. Hazel gets a job at Paddington General Hospital and finishes her midwifery training, then goes out on the District, on her bike, much like the people you will have seen in ‘Call the Midwife’. Gillie comes down and gets a job after agreeing that his fiancé Margaret will join him later. In 1950 Hazel and Ally and Margaret and Gillie have a joint wedding at St Matthew’s church on St Mary’s Road, Harlesden, where Blanche has a house. Hazel and Ally buy 81 Keslake Road, Kensal Rise and Margaret and Gillie move in there with them.

The joint wedding. Fred, Rose, Glennis Doughty?, Ally, Hazel, ?, Annie Morgan, Mavis Livesey, Blanche Livesey, Idris Morgan, Gilly Livesey, George Livesey, Gillie Scott, Sylvia Doughty? Margaret (Montmorency), Nanna Montmorency.

Here is another family gathering at Blanche Livesey’s house in 1955. This event was probably sparked because of the visit of Bert Scott and Sarah from Canada. Peter Scott is down at the front (no13) with his family behind. The Mcleod’s are related to Peter’s mother and now live in Canada. Two years after this photo, I was rushed away from this house in an ambulance on Boxing Day, having attempted to cut my hand off by falling through a glass door.

1 Mavis Livesey, 2 Stuart Mcleod, 3 Blanche Livesey, 4 Billy Mcleod, 5 Fred Scott, 6 Peter’s mum Josy, 7 Sarah Scott, 8 Bert Scott, 9 Rose Scott, 10 Peter’s grandma Fanny, 11 Arthur Scott, 12 Gladys Mcleod jnr, 13 Peter Scott, 14 Gillie Livesey, 15 George Livesey, 16 ? 17 ? 18 ?

This migration seems to have been part of a wider movement, as I remember other Barrovians down there who were just friends. Of course, London has always attracted people looking for work from all over. Much as Blanche had provided accommodation for others, at some point, dad divided the downstairs front room into two rooms, as it had a window at both front and back and these two rooms were rented to Reg and Jean Harris, so there were three couples in the house. I think that Blanche and George had managed to buy both the flats in one house on St Mary’s Road and the upper one may have been used by various people. I think that is where the actor Peter Swanwick lived when he came down from Nottingham to act in the African Queen, which is how he and Nellie became family friends.

Back up in Barrow Fred and Vera had their first child (Cheryl) in 1950 and then decided to up the travel ante by moving to Detroit, along with Vera’s mother and father. Just before all this, in 1948, Violet Morgan decided she had had enough of being ignored as a nurse. Who knows, the formation of the National Health Service that year and its proposals for staff may have been the final straw that sent her packing. The upshot is that she emigrated to Australia and that story is worth telling too. For the moment though, we’ll leave the story here. I’m on the way, the mother of my two daughters (Jacky Rooks) has been born. There is plenty more to tell.