In the Science of Discworld by Terry Pratchett, Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen, they introduce the idea of ‘lies to children’ to explain how at every level science education doesn’t tell the whole truth because it is too complicated. When I was at school, I studied Social History and we covered such things as the Enclosure Acts, the Agricultural Revolution, the Corn Laws, Chartism, Education Acts, Industrialisation and much more. Writing these stories has led me back to those subjects and made me realise what a simplistic view we were given and how little I understood of that. In the first part of this story, I included a map of land tenantship and the narrow strips of land made me think immediately of the Enclosure Acts. I now realise that this change in land use wasn’t an overnight process but took place over several centuries and at different rates in different parts of the country. In this part of the story we start out in the countryside around Lichfield, Staffordshire, just south of the village of Shenstone. Below is a map Lichfield in 1781, around the time the oldest people in this story were born. Lichfield is an ancient place that has kept much of its history. After reading this story a friend said that she had spent some of her early years here, as her father was a semi-retired Anglican missionary and clergyman who was ‘master of St Johns without the Barrs’, which is the last large dark shape on the bottom left of this map. This is a Christian Almshouse that has existed here for nearly 900 years. If you look at the map you will also see that there are lots of small strips of land. This pattern reflects an ancient way of life, where each family might rent a small patch of land and have a small house on it, as well as keeping some livestock and growing some food.

In this part of the story we will see some of the effects of enclosure and selling of land, the growth of the railways and resultant share ownership, knock on effects from the Napoleonic Wars and the growth of steamships and large-scale agriculture in America and all affecting a line of ordinary people called Scott and those who got involved with them. On our theme of travel, it is worth mentioning that if your family name is Scott, then, at some point a male side of your ancestors came either from Scotland or Ireland. While we are on the theme of names, it is worth mentioning that part of this story starts from the bible given to Sarah Whorwood and dated 1827. That book has been passed down the line, but not the female line, the male line. That in itself reflects one of the problems of histories like this. It is often hard to create a picture of the women involved, because they are not characterised by different jobs with different lifestyles. All the Census and Electoral Role information is based on assumptions about gender and name changes make it more difficult to trace daughters. When my researches led me over the Irish sea, I suddenly realised that the tracing task was often easier there, because the Catholic Church wanted to keep a better grasp on its flock, so recorded details like mothers name before marriage. The biases in history are at odds with my own experience of life, where, while they worked hard and were generally good citizens, the men were really secondary to the women in making life run smoothly. I will try to reflect that where I can.

Scotts and Herberts 1781-1871

The future Admiral Sir William Parker 1st Baronet of Shenstone was from a powerful Staffordshire family and went to school in Lichfield, so, as his fortunes rose, he bought Shenstone Lodge and areas of land around Footherly in around 1810. Him and his family are hard to trace in records because they move about and have more than one residence. A more assiduous researcher than me might be able to paint the picture more clearly. There are also multiple people with the name Neville in this area and there are references to them in Shenstone hundreds of years back, so William Parker may have bought some of the lands from this family. The Scotts seem to have worked for both of these families.

These were lands that where parts were being sold off as country estates. In one transaction I came across, a parcel of land was sold off, together with a pew in one of the churches. I suspect that the workers on such estates often lived on small plots on the estate and transferred to the new owners. Two such staff were John Scott (b1781) and his wife Ann (b1786). John was described as an agricultural labourer at Shenstone Lodge. The census records are confusing, because the place/residence names seem cover multiple households. I can see no mention of William Parker on the census, though he owned Shenstone Lodge for many years. It is possible that the Scotts were listed as resident at Shenstone Lodge while the Parker family were living elsewhere.While the big house looks grand, the agricultural workers would have lived on small plots on the estate that might have looked more like the one at St Fagans Museum of Welsh Life. The page below gives a good picture of the sort of conditions.

https://museum.wales/stfagans/buildings/nantwallter/

Ann and John had three sons, George, John and James (1819,1821,1826). George was my great, great grandfather, so tales have been told. He was baptised in the ancient church of St John the Baptist in Shenstone. Lichfield itself is an ancient place and, being the meeting point of major Roman roads, was a still a major coaching and carting centre in the eighteenth century. It has Roman ruins at Wall and the largest ever Saxon hoard find in the UK. As industrialisation advanced, Lichfield would fade into the background as places like Birmingham grew. As George grew up, it looks like more lands nearby were being bought by industrialists and foreign traders, who wanted to be gentlemen farmers. There is an area just south of Shenstone Lodge at Shenstone Woodend and by 1841 George and his brother were working there, probably for Thomas Neville. Shenstone Woodend is very near Sutton Coldfield.

At one point John and Ann are referenced as living at The Lodge Woodend and there is now a restaurant at that address, but I doubt this is the same property.

St. John the Baptist church.

Lichfield, Shenstone and Sutton Coldfield

Sarah Whorwood was born in Sutton Coldfield in 1816. Her father was Thomas Whorwood (probably died 1840’s), who was described as a Wire Drawer and her mother was called Ann (b1773, d1851) and her grandfather was called Thomas Whorwood……

There seems to have been a few Whorwoods living around Whorwoods Field, which was probably near Langley Hall, on the southeastern edge of Sutton. The name Whorwood apparently has the same origins as Hereward (like the defender of the Anglo Saxons against the Normans). If you were an unpleasant racist rewriter of history, this is probably the name link you would cling to. The Whorwoods were apparently cordwainers (shoe makers) and seem to have been in Sutton in Coldfield since around 1600 and before that down in Wishaw, where the Belfry golf course is. Interestingly the main road through Wishaw is the Lichfield Road that runs past Sutton on its way up to Lichfield, so that was probably a well used trading route. There was a Toll Booth on that road at Shenstone Woodend.

All the Whorwoods were baptised Anglicans in Holy Trinity, Sutton. There is a line running through the town till today and one descendent was Jim Whorwood, a long standing councillor, Mayor and Alderman.

How George and Sarah met is not clear, but they married in St John the Baptist church, Shenstone in 1844. Sarah’s older sister (by 11 years) Ann Francis and George’s brother John were witnesses. George and the two witnesses made their marks but Sarah signed her own name in a strong hand. Sarah moved in with George at Woodend and by 1851 they had the first three children, Ann Elizabeth, John Thomas and Joseph. George’s mother Ann was living with them, father John apparently having died in 1846. On Joseph’s birth certificate George still made his mark, rather than signing and was described as a labourer. According to the family tale, put in writing by his daughter Ethel, Joseph sung in the choir at Lichfield Cathedral and even went to St Pauls to sing. Being attached to one of the big estates, makes this quite likely. The family bible has another child Samuel Scott as well, born in 1852, so invisible on the census of 1851 and hard to pin down thereafter. He disappears but is important because he pops up in family stories later. I dubbed him Samuel Scott man of mystery but have later managed to track him down a bit better. He seems to have been born in 1853 and is registered in Birmingham, but I think Sarah had gone to stay with one of her relatives, either in Sutton or in Birmingham itself. George was living separate to the family as a servant and, as her mother had just died she must have felt the need for more support with three small children and a fourth on the way. Samuel is eventually baptised back in Shenstone in 1857. Even his birth took some tracing. The 1861 census seems to have disappeared for that area, but by 1871 George was described as a farmer of 28 acres at Footherly and Joseph and John had disappeared. Ann Elizabeth was still there and described as a nurse. John Thomas looks as if he died in 1863. George was not on the Electoral Register, which means he did not own the land. Land ownership was the qualification for the Register until 1918. Ann Elizabeth marries George Giles Taylor in 1873.

In the 1871 census, Samuel is working as a groom for a doctor in Market Street, Lichfield, which is opposite St Mary’s church. I suspect it is from here that he is poached by a retired clergyman called Luke Jackson who was born in 1788 and for some time seems to wander around visiting other clergymen. It could also have been his son Curtis, who is a working Clergyman and living with his father and sister at the time. There is no proof of this but the sequence of places, people, job roles and cross references makes me fairly certain I am tracing the right Samuel, having investigated many false trails. Tracing back from Barrow leads to the same conclusion. Luke Jackson was vicar at St Mary Magdalene church in Hucknall Torkard in Nottinghamshire. I am guessing, like me you have never heard of the place, but it is where Lord Byron is buried and, alongside him, his daughter, Ada Lovelace, one of the worlds most famous mathematicians, who worked with the computer pioneer Charles Babbage. I will come back to the connections later

In researching the mysterious Samuel Scott, I went on family tours of Admiral William Parker and Thomas Neville, who lived at Shenstone Woodend, trying to find what servants they had at various times. That search is not easy. Admiral Parker, for instance, was often zooming around the world on ships and his family would decamp to other places too. At one point I came across most of his children in a census for an Admiralty run residential school in London. That means that servants on the estate were left to their own devices, with a minimum staff maintaining the land and buildings. Also, crossing the period we are considering here, the Admiral died and in the process of dealing with his estate Thomas Neville moved into Shenstone Lodge and the Admiral’s son moved into Woodend. I am surmising that some of the land at Footherly was rented in small parcels to the servants who occupied them in the estate. That might explain George’s late change of status.

It is worth putting in a bit of history here. The American Civil War ended in 1792 and thereafter the new country set about colonising the countryside more steadfastly, setting up farms based on large fields, more modern agricultural practices and on the use of machinery and good transport networks. Especially encouraged by the development of Steamships after 1820, the new nation started to send its cereal products all over the world. The response from the British government, partly in a huff about losing their colony I suspect, was a series of Trade Tariff wars, known as the Corn Laws. The effect of these was to make rich landowners richer and more powerful, so those who had made money from the early industrialisation wanted to cash in on it, encouraging more Enclosures and the growth of more, smaller estates owned by these ‘Nouveau Riche’. Ironically the effect on the economy was devastating. The poor got poorer and were not only eating less, but also buying less, so depressing trade. The agricultural economy went into depression and Industrialisation stalled. When the Irish famine came along, starving those who had already been dispossessed of their land in the earlier Plantation colonisation from Scotland, the strain on agriculture became too great and the Corn Laws were repealed in 1846.

Not all industries had stalled because of this political madness. Ship building had flourished and the railways had continued to grow, as we saw in our story involving Wales and Cumberland. During the time of this current story, Barrow-in-Furness had emerged as a centre for Iron, Steel and Ship Building and the town was growing, though not at the same pace as Manchester and Birmingham. It seems to have attracted quite few people from the Midlands. Barrow is cut off down at the bottom southwest corner of the Lake District. At this time the Lake District was still viewed as a wild place and it was only the likes of William Wordsworth and John Ruskin who would change the popular view. Barrow was in Lancashire until the 1960’s.

Scott and Smith 1871-1901

There is a Joseph Scott working as a butcher’s assistant in Wolverhampton in the 1871 census. The butcher was a widow, called Sarah Smith and Joseph soon marries a woman called Adelaide Smith in 1877, so I suspect that Sarah Smith was Adelaide’s uncle’s widow. Interestingly, by the time of the marriage George Scott is described as a Gentleman. Presumably farming 28 acres merited this new status. Adelaide’s father was a railway inspector and that family appear to have moved around from Walsall to Lichfield and then to Burntwood Green, west of Lichfield, with his job. Adelaide was a dressmaker and Joseph and Adelaide were my great grandparents. By the time of the marriage, Joseph was already living in Barrow-in Furness and working as a Layer of Services.

By the 1881 census in Barrow, Joseph is described as a Gas and Water Inspector and he and Adelaide had their first two children, the first not surviving. Soon after the marriage Joseph’s parents George and Sarah moved up to Barrow too.

George and Sarah were described in the 1881 census as shopkeepers. In 1883 Sarah died aged 67 and in 1891 George was described as a Cowkeeper and living with Joseph’s family. He died in 1898 aged 79. It is worth remembering that old age pensions were not introduced in the UK till 1908, so older people had to earn their own living, rely on family or go into the workhouse. By 1881 Samuel is working for the recently deceased Luke Jackson’s daughter Isabella Jackson as a butler over in Hucknall, Nottinghamshire

Joseph and Adelaide had nine children in all, though some died in childhood. My grandad Frederick Charles Scott was the eighth to be born in 1889. By 1891 all six surviving children were born and George lived with them as a widower.

Eleven Fenton Street, where three adults and six children lived.

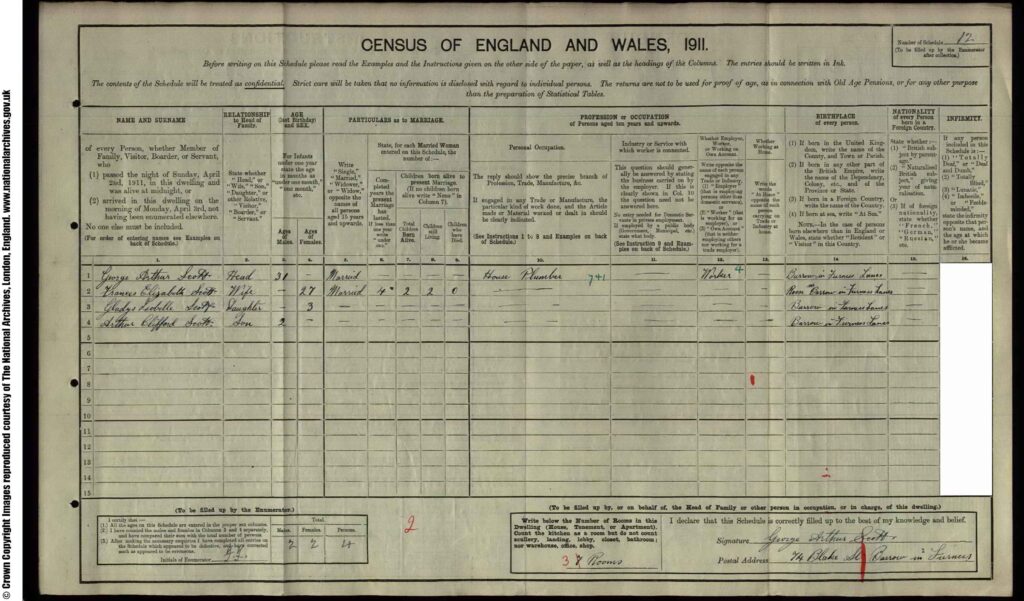

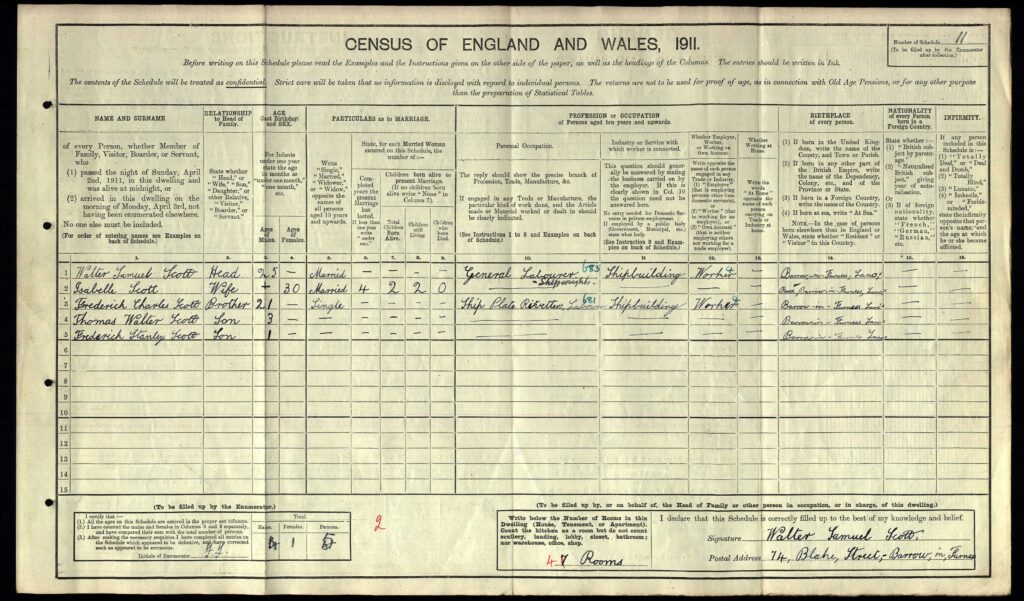

The family were still living at Fenton Street in 1901 but Adelaide had died in 1896. A widow of Joseph’s age, called Elizabeth Tyson, now lived with them. Over the next few years the older sons and daughters would start to marry and move out. George Arthur had married Frances Falshaw, Walter marries Frances’ sister Isabella and he and George have separate households in 74 Blake Street by 1911. The house has seven rooms, with 4 for one household and 3 for the other in the census. Both George and Walter were plumbers who worked for a firm called Silvermans. Later George’s son Arthur Clifford also apprenticed with the firm. Arthur Clifford was Peter Scott’s dad and Peter has helped me with this project. Here are the census records:

The house at Blake Street has disappeared But here is another one as an example. In what is called the 1939 Register, Peter Scott’s maternal Grandfather was living at 129 Abbey Road, which is quite a nice four storey building.

When you look a the actual census sheets you see how many families were in the same house. As older offspring moved out, other people moved in to help cover costs and this pattern continued throughout the war and beyond. Peter remembers an old lady still living in the front room in 1952 and his uncle was a Japanese Prisoner of War, so his aunt moved into the house too. In the way that these things stay with you, he has a vivid memory of the smell of the cellar. We will see this pattern repeated later in the first house I lived in.

After the war Arthur Clifford Scott and family moved down to Bexley Heath, where Peter Scott was born. Connections between the Barrow exodus families were still reasonably strong. My aunty Blanche was particularly one for keeping in touch, as demonstrated by this photo of her daughter Mavis with the one year old Peter Scott at the house in Bexley Heath.

Incidently the 1939 register was used up and beyond the year I was born for ration books and similar items, so sometimes the names change (a bit Big Brother like), or are redacted when the person dies, as above. The Blake Street house may well have been similar, but there were still only seven rooms in total for two families and boarders.

Another of Joseph’s sons, Herbert, or Bert as I remember him, ends up in America around 1907, marries a Sarah Gill from Bolton in 1910. They live in San Francisco at first and by 1917 Bert is registered for the WW1 draft in Letcher, Kentucky. There is a family tale that Bert was a Dresser to a Hollywood star, but the timescales and places seem slightly adrift, though possible, and he was on the right coast. The star may have been Ethel Barrymore, part of an acting dynasty who all moved between theatre and film and a variety of locations, including Hollywood, New York and London. When he registers to visit the UK in 1924 he is already a Presbyterian minister, which he remains till his death in Canada in 1973. Sarah dies a year later and they are both buried at St Andrews Cemetery, Niagara Township. There is a story that ex Canadian Prime Minister John John Diefenbaker spoke at his funeral, which is vaguely possibly for reasons of religion and location.

Herbert Scott’s Passport to return to the UK for a visit in 1924

Adelaide marries Wilfred Kipling, a bricklayer, and by 1911 Joseph is living with them. Ethel disappears off somewhere and apparently marries in 1920. The letter she wrote George’s grandson Peter Scott was sent from Bolton. In the tales of all these relatives I know there is more wandering about from place to place. Frederick we will come to later.

It is worth taking a side step back to our man of mystery, Samuel. In 1883 a Samuel Scott appears in the Electoral Rolls for Barrow owning one property which is a hotel at the property below.

At first I thought this was our Samuel Scott, after all the family story is that he went round in a Rolls Royce and put money in trust for Joseph’s children, so this one was worth investigating further. Sadly it was a different Samuel Scott, born in Westmorland. My growing experience in this searching business allowed me to tie the property with a census record and then to trace the electoral rolls through. What added to the confusion is that the other Samuel Scott suddenly becomes Samuel Scott Senior, then moves house. He also owns property on one of the same streets. as our Samuel, who appears in the years after 1908, owning three properties. I am tempted to re-dub him Samuel Scott, Man of Mystery and Slum Landlord, as the properties are all very near Barrow Island and the areas around there were known for greater levels of poverty and also of Catholicism, with many having moved over from Ireland. In our Samuel’s case his residential address is at Grafton Court in Alcester, Warwickshire. At first I thought Samuel had moved up to barrow and his son was working at Grafton Court. The other family story about Samuel is that he was a butler and we saw that he was working as one in 1881. By 1891 and still in 1901 a Samuel Scott is listed as living in Grafton Court with the family of Dominick S Gregg, first as a butcher and then as a butler. When I thought he had a son Samuel, I also spotted that he had married Clara Richards (b1860) at Grafton Court in 1909, but the son also seemed otherwise invisible. Later I realised that the woman who married Samuel in 1909 was actually of similar in age to our first Samuel and she had worked with him for Isabella Jackson in 1881. None of this reduced the air of mystery surrounding Samuel, but did add weight to the family story.

Of course I couldn’t quite let it go, so I kept coming back to it as I researched other stories. Finally I tracked it down to my satisfaction and the story is a good one.

First let’s look at Samuel’s moves from Lichfield to Hucknall Torkard. First there are strong connections between Lichfield and the other side of hills. There is a direct road between Lichfield and Derby and strong religious connections through the Church of England. During the Industrial Revolution this whole area was a hot-bed of invention and change. Charles Darwin’s grandfather Erasmus was a one time resident of Lichfield and was connected with developments in Derby. Movement between towns and close connections seem to have been quite strong. It also so happens that the doctor Samuel works for in Lichfield is a shareholder in the Great Western Railway and that Curtis Jackson from Hucknall Torkard is also a shareholder. If you have spent as much time as I have looking at the household staff of the well off in this period, you soon notice that these staff come from all over and it is obvious some of the movement comes with the families taking staff with them on visits, or poaching staff when necessary. It so happens that Luke Gregg also lived on the income from his shares in the Great Western Railway, so we have another connection via shareholders meetings.

After marrying Clara and leaving Grafton Court, the pair move to 9 Willes Terrace, Leamington Spa.

In the 1911 Census they are both described as of independent means. How did they achieve this? Well, within the Carlile family, and thus in the Gregg family, there was a tradition of rewarding loyal servants with incomes or cash sums. I suspect this may be what had happened. Both James William Carlile (Alice Gregg’s father) and Dominick Samuel Gregg died at Temple Grafton in 1909, so there may been some changes and planning for some time and sorting out his affairs. In the same 1911 census Samuel and Clara have two visitors living with them. One is Dominick Carlile Gregg, the son of the family at Grafton and the other is his valet John William Smithson. There are no children and, sadly, Samuel dies in 1912. After nearly 30 years of affection, they only had three years together. Samuel’s will is placed in London and leaves money only to two others.

I suspect he was using the Gregg family solicitor and had already put the houses in Barrow in trust for Joseph’s children. There is nothing for Clara but she is still living in the same house in 1921. By then she has a companion, called Ella who is the niece of the valet who was visiting in 1911. One explanation is that Samuel’s will left the house and some finances to Clara and the proceeds from the sale of the houses in Barrow to be held in trust for his nephews and nieces.

In 1921 Clara, her companion, John William (the valet) and Dominick Gregg junior are all listed on the Electoral Roll for the house. Right to the end Samuel and his dealings throw up more questions.

Clara also dies in 1922 and in her will she leaves a total of £505 10s, shared between the valet and William Henry Richards, Gentleman, who is her brother and is a confectioner back in Hucknall Torkard. By this time they have all moved round the Corner to a bigger house on Willes Road.

Dominick Gregg dies in 1935 and John William Smithson moves back to Aylsham in Norfolk, where he was born.

When you start looking at all the people involved in that story and inspect the hints about their lives more closely a pattern emerges. Isabella Jackson never marries. The census when Samuel is with Isabella has her niece living with her. Her niece, Mary C Jackson, is described as a landed proprietess at the age of 40 and single. By the 1901 census Mary C is described as visiting a woman called Geraldine Chermside, who lives in Byron’s former family home. She married a renowned army colonel/major/major general just two years before, but the two of them never seem to cross paths again and there are no children. Her house has a staff of 7 women and two men.

After the 1881 census Clara Richards seems to disappear, but may be living in the tiny village of Colston Bassett, where there is a single ratepayer (property owner) of that name.

My suspicion is that there are various relations involved here that are outside marriage and that Clara and Samuel’s marriage was one of convenience. The families are keeping these things buttoned down in various ways and people involved are aquiring property accordingly. The patterns are not the same as family movements I have seen elsewhere.

In an interesting circle of connections, the house at Grafton Court was gifted to Dominick Gregg’s wife Alice Woodhams Gregg (formerly Carlile) by her father James William Carlile. Before marrying Dominick, Alice lived in Meltham, where my own little branch of the Scott family lived for a while as well. There is a Carlile institute in Meltham. Her father also rebuilt the local church and several of the village’s houses. After leaving Meltham he starts setting up another village idyll but than moves in with his daughter at Grafton Court. He and Dominick Gregg both die in 1909. James Carlile leaves an annual stipend to his butler, which may have been Samuel. When Alice Woodham Gregg dies, the house is left to her Daughter, which may also throw light on the Scott/Gregg move to Leamington.

Taylor and Scott 1900-1928

Rose Annie Taylor was born in 1887 in Birmingham. Her father William was a boilermaker and was born in that area in1858. Her mother was Mary and she had been born in 1857 in Northamptonshire. There were six children in all. In 1901, at the age of 14, Rose was already working as a domestic servant. Over the next few years she would work in service in Hotels in the Lake District. At some point she was working with a really good cook who was a heavy drinker and very secretive about her recipes. Unfortunately when she drank she became less capable of cooking and had to let Rose assist her and even take over. In this way Rose herself became a good cook, a skill she would pass on later.

While she was in the Lakes, Rose apparently got engaged to a policeman from Coniston, but he sadly died. I suspect that Rose came back to Barrow in 1911, to look after her father when her mother died that year.

Frederick Charles Scott started work in Barrow Shipyard at the age of 12 in 1902. If I remember rightly he told me that he was allowed a full egg on Sundays as a reward for bringing in a wage. Throughout most of his working life he was the person who held a red hot rivet into a hole through two steel plates, so the riveter could flatten it on the other side. One of my favourite artists, Stanley Spenser depicted the activity when he painted in shipyards during the Second World War. What Stanley doesn’t depict is the task of getting the fire, fuel and rivets up to wherever you are working in a vast ship before you can start working and getting paid.

As grandad was nearly 70 when he retired, he will have held up a lot of rivets. One of the first ships he will have worked on was the cruiser Rurik, built for the Imperial Russian Navy over the three years from 1905 to 1908. Trials showed weaknesses in the structure when using heavy armaments and so changes were made to the structure in the ports at Kronstadt, on Kotlin Island, in the Gulf of Finland and near St Petersburg. Some of the strange tales I remember as a child were about playing football with the ‘Ruskies’ and endless meals involving cabbage. This all made sense when it became clear that grandad had been to Kronstadt to help rebuild the ship. Like many of the family travellers he came back. As the Russian Revolution was less than 10 years away, that was probably a wise decision. How he got there and back is unknown to me. By 1911 grandad was living with his brothers in the Blake Street house.

When I was little Grandad Scott always sang a snatch of ‘waiting for the Robert E Lee’ when he first saw my brother, frequently quoted ‘I walked across a knapsack with a field upon my back’ and often said ‘now then Jack, get this down thee flick flack. Rise up an fight the dragon again.’ As all sensible children do, I paid no heed to this nonsense. As I say in the overall introduction, many years later I was watching a friend perform in a mumming play in Sowerby Bridge, in Yorkshire, and the character of The Doctor, in an outfit covered in scissors and other medical instruments, repeated some of my grandad’s nonsense; ‘Now then Jack, get this down thee flick flack. Rise up and fight the devil again’. When I asked my dad, he confirmed that grandad had indeed performed in mumming plays and worn such a costume, in Barrow-in-Furness in the early 1900’s, though my dad wasn’t born at the time. I don’t know when exactly grandad started and finished doing the Mumming Plays, but he was part of a trend current at the time. At the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth centuries there was a big revival of folk events and activities across the UK and mumming plays were part of that. The history of these is vague, but Midsummers Night Dream has what looks like such a play as one of its central strands. There was another revival of them in the 1970’s and Furness Morris Men still perform an ‘Easter Pasche Egg play’ in Ulverston today. Below is my picture of The Long Company mumming play in Sowerby Bridge.

Rose and Frederick met and married in 1912. Over the next fifteen years they would have seven children, the last of whom died within a year in 1928. Not surprisingly Frederick didn’t take part in the First World War, as he was busy building ships and submarines.

In the next parts of the story we’ll look at the further adventures of Frederick, his siblings and the six remaining children.