When I started this project of writing down some family stories and trying to check them against the genealogical facts, I had no idea that I would enjoy relating the stories to the wider history. I also had no idea that it would in turn bring some of the wider history into relief as well. Although Ruth and I have no direct family link and my grasp of her family stories is very shaky, I decided that I would at least start some of the research, if only because her dad and mine were in Northern Ireland at the same time during the Second World War. What I didn’t realise was how much it would once again highlight how wider histories have such long lasting effects on people just getting on with a day’s work and feeding a family.

As I started to look through the records, I was finding it hard decide whether to look in Ireland or Britain. I know a bit about Irish history and was used to allowing for the change when Southern Ireland became independent in 1921 (incidentally the year of Ruth’s Dad’s birth.) The revelation that came suddenly in looking at the records was, some might say in a typically English way, I was looking at it all the wrong way. What actually happened was that Ireland continued to exist, but with some changes in management arrangements and an entirely new thing came into being, carved out of six of the nine counties of Ulster. The six counties were decided on for no other reason than to ensure a Protestant majority. Although it was several years before the border was agreed on, one bit of that border, the river Foyle, ran past Ruth’s family’s farm. On the ground, that meant that different parts of the same family, and even of a single farm, were often suddenly in different countries. I’ll come back to some of the effects of that later. First, I want to take the general history back a bit further.

The domination of Ireland from over the water goes back a long way and contains many twists and turns. It is too complicated to do justice to here, but I’ll sketch it out and try to draw out some issues that have knock on effects on the families and their relationships with other people on the island. Not surprisingly, religion comes into it, but also language. Like the situation we came across in Wales, both religion and language were used as means of discrimination in pursuit of wealth, power and control. There are practical issues like control of borders and trade. There are also abstract issues like sovereignty, loyalty to country or religion, the divine rights of kings and queens, that are written and talked about by persuasive people, but are often acted on by ordinary people. The knock-on effects can be very unpleasant and even deadly.

You may well ask ‘what has this got to do with family history?’ Well, one of Ruth’s granddads was called John Knox McCombe and John Knox was a leading figure in the Scottish Reformation that led to the banning of Catholicism in Scotland. That name goes beyond being just a pious statement of loyalty. Similarly, one of Ruth’s childhood memories is of sitting in a car back seat, crossing the guarded border, with dairy produce under the seat to avoid detection. I have heard family tales of gun caches and people ensuring a farm sale went to the right people. These abstract notions have everyday consequences at all levels, as we are seeing in the present day with the post Brexit situation on the border in Ireland.

When I was looking at Ireland in a previous history, Wicklow was a problem area for the English in the 18th and 19th centuries, so they tried to control it by force and discrimination then finally tried the softer approach of emancipation.

In an earlier century, one of the most problematic areas was Ulster, which then covered the whole northern area of the island of Ireland. Here there were wild Gaelic speaking natives, controlled by Feudal Lords and predominantly Catholic in religion. After what was called the Nine Years War, the Lords and Chieftains were largely expelled from the country and King James the first (originally King James the sixth of Scotland of course) commandeered the lands, handed it out to his own and encouraged them to rent it out to, protestant, non-Gaelic speaking people from Scotland. In practice that largely meant English speaking Presbyterians. The ordinary Irish people largely stayed but had just moved further down the rungs. Although his mother was a Catholic, James himself was brought up in the Calvinist Church of Scotland. After he started theorising about the divine right of Kings and acceded to the English throne, James moved further towards Anglicanism and started to alienate the more Calvinist members of his population. In one of those odd circles of coincidence we stumble across in these histories, one of the first things James did, on accession to the English throne, was to clear out the border Reivers who had for long run wild in the area where Scotland bordered England. These Reivers were transported to ‘the wastes of Ireland’. My family’s locale in Cumberland was protected to the potential cost of the island of Ireland.

King James was followed by Oliver Cromwell in the endeavour to purge Ireland of Catholic practices. Cromwell’s puritans wanted the Church of England to get rid of some of its more Catholic practices and to deny the right of Kings and Queens to overrule parliament, but he was also generally tolerant of other Protestant faiths.

After monarchy was restored, the unpleasant and catholic, King James the second asserted his divine right, prorogued parliament (his sovereignty was supreme, not theirs) and started to punish non-Anglican protestants for what they had done. This in turn led to plotting and intrigue and invasion by the Dutch/Anglo William of Orange and his wife Mary who finally defeated James on Irish soil. This victory is still celebrated today by Orange Orders, parades and entire villages declaring their loyalty with multiple flags.

The, now British, rule of Ireland treated Presbyterians similarly to Catholics, in that they were not allowed to sit in Parliament. As pressure later began for independence in Ireland, Presbyterian plantation settlers in Ulster were worried that ‘Home Rule’ meant ‘Rome Rule’. With emancipation and the right to buy land, remaining worries about British rule disappeared and the fear of Catholic domination increased. You might think this fear is excessive, but Pope Pius the fifth issued a bull against Queen Elizabeth 1 and declared that people could not be good Catholics and loyal to their Queen. Some of the post-partition events and excesses of Catholicism in independent Ireland, served to support that protestant fear.

From this we see a split developing between Ulster and the rest of Ireland. Independence and Home Rule movements were as much Protestant as Catholic outside Ulster. But also, there was more integration at an individual level outside Ulster. In another family story there was evidence of Welsh immigrants converting to Catholicism to marry. There were also protestants of obvious Welsh extraction in the Home Rule movement. Other Protestants included Quakers and Huguenot settlers, who also integrated well. The Huguenots in particular, became central and helped make Irish Linen famous and were also the founders of what became the Bank of Ireland. There is an Irish Linen Museum in Lisburn, southwest of Belfast, based round what was originally a Huguenot business. In one of our little family coincidences, the Lisburn Huguenot Louis Crommelin has a style of cloth named after him that leads you straight to Huddersfield if you look it up on the internet.

A quote from the museum provides an interesting insight into what is an unavoidable undercurrent to any history, family or otherwise, of this region.

“At the beginning of the Decades of Centenaries in 2012, there was a recognition amongst the research staff in the museum that while there was a good understanding of the contribution of Lisburn’s Protestant population to the Great War (1914-18), there was little known about the role the town’s Catholics played in the conflict.”

It always comes as a surprise to most people outside Northern Ireland to find that a very large majority of Education there is still split by religion. This is often by choice within communities and continues the tendency that existed across the island of Ireland before partition and in England, to a larger extent than now, before education was reformed. When Ruth went to a Protestant school in a largely Catholic area, she didn’t witness many riots, but she was constantly aware of the threats to her, in her noticeable school uniform. On the other side, I have heard people tell of surrendering old family caches of arms under one of the many gun amnesties. This and many other factors mean that Northern Ireland is still strongly divided, though the split is not always obvious at first to the casual visitor.

The family history outlined here will be largely a protestant one, based round the border between Donegal in the Irish Republic and Tyrone and Derry on the other side. I will try to tread carefully through areas where the cultural/religious split is unavoidably present in the evidence, but I won’t shy away from highlighting it. Researching this story has made it obvious that there are sources of information on the internet that are not reliable, because they have an underlying political/cultural stance. I have tried to tread a reasonable line through this.

Tyrone 1700-1921

At the start of the eighteenth century most of the land in the area around Ruth’s family farm was owned by a family called Hamilton, who have had various and multiple peerage titles in Ireland (Earl, Marquis, Lord etc. of Abercorn, the irony being that Abercorn is in Scotland) since the time of King James the first. An earlier member of the family was also styled 1st Baronet, of Donalong (who incidentally was brought up a Catholic), which is an area we are particularly concerned with. These people mostly were born, lived and died in Scotland or England and their affairs in Ireland were managed by various less important members of the Hamilton family. Hamilton is a name that crops up in lots of the records for this area. The line and titles still exist and they are one of only two remaining lines with a string of titles in all four of the countries that make up Great Britain and Northern Ireland. At various times they have also laid claim to the French title Duke of Châtellerault.

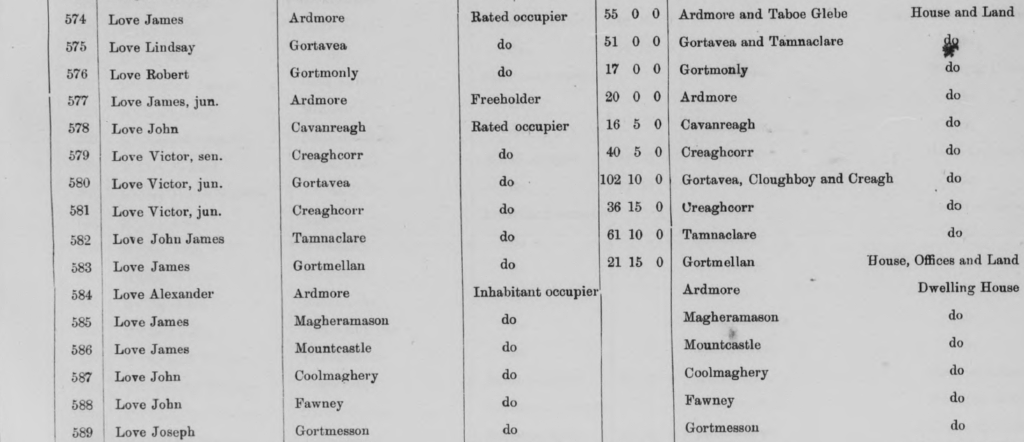

During the same century the area around the river Foyle and between Derry and Strabane is populated with large numbers of families with the surname Love. The name is often assumed to be Scottish, and the families may have come from Scotland, but there is some evidence that it came into Scotland from England. It is one name amongst many others that can also still be seen today. In a thing called ‘W.P.W. Phillimore & Gertrude Thrift, Indexes to Irish Wills 1536-1858, 5 Vols (1909-1920)’ and dated 1831, the following can be found for the earlier Loves:

In that area Dunnalong is a Townland and larger Electoral Division. These families either rent small farms from Abercorn or sub-rent smaller properties from other families who do. Many of these families are growing Flax and documents can be found that list the number of spinning wheels and or looms per family. Before the flax is ready for spinning, it goes through around eight different processes to prepare it. All these processes and the spinning can be done on the farm. The resultant yarn is then sent to be woven into cloth. Bigger farms were able to support looms as well.

Later in the eighteenth century, Flax Mills were built next to rivers and many of the processes were taken over by machine. I stumbled across a reference to a flax mill in the Altrest Townland, southeast of Bready (and so southeast of the Love farm of today) as late as an 1858 land inventory. At first it seems unlikely, as the river doesn’t pass there, but closer inspection reveals a smaller waterway that would have served the purpose. The move from homework to feeding mills with product would have been gradual and the changes in lifestyle, creating a split between farming and manufacture, town and country, would have followed. This area is not like the crowded areas of West Yorkshire and Lancashire that were covered in an earlier story, so the transition may have been less drastic. The east of Ulster will have been different again.

Finding the right Loves

There are George and Victor and Victor George Loves both east and west of Derry in the period we are interested in, so they are no doubt related too. The Love farm, south of Derry that we are concerned with has been called Foyleside, for an obvious reason, for a long time. Unfortunately, a large shopping complex in Derry is now called that, for the same reason, and that makes searching for the farm on the internet like looking for a needle in a haystack. It is better to use the names of the Townlands. The most relevant for the farm is Gortavea, though it crosses into three others. Early in the nineteenth century a George Love is living at Gortavea. He can be seen listed in the attached records from the Irish Valuation books for 1833, along with the Rollestone’s (or some spelling variation) who also still farm next door.

George’s father was called Victor, so he called his son Victor. That Victor called his son Victor too. There was a Victor Love living on an adjacent Townland and more on nearby Townlands. There were plentiful Loves nearby with other names too. Ruth’s grandad was called Victor Moorhead Love and her dad was George Victor, but everyone called him Victor anyway. Can you guess her brother’s name? Searching the scant records online becomes highly confusing. In the South, Catholic institutions were obviously more desperate to prove to higher powers that they had a grip on their flocks, so kept better records, including mother’s name before she married. There are also many more censuses available down there. Altogether it is easier to be sure what you are finding by cross referencing between different sources.

In a thing called Griffith’s Valuation for 1858, you can see that some people are starting to buy their land and to sub-let parts of it.

In this edition of the Valuation George does not own the land. There is a Victor Love on the neighbouring land at Creaghcor, as well as a David Love and neither of them own the land either. My guess is that Victor and David are sons of George. There are no Loves owning or renting land on adjacent Cloghboy. Who does rent land in all the relevant places is Isaac Daniel. I can find no other reference to him at all in any of the records, so my guess is that this land was what was later rented or sold to Victor Love. There are other Daniel’s in the same area and there are plenty of Donnel’s nearer Strabane and over in Donegal, but no Isaac. One possibility is an Isaac Doherty who dies in 1872. I have put him in the table below of all the Loves in Dunnalong over time.

Around the 1870’s onwards, reports come in of a Victor Love buying his land from Abercorn, representing ‘the people’ in the building of a Presbyterian Church in Magheramason and in the paper for attending the General Presbyterian Assembly for Ireland. A George Love dies in 1879, so the assumption could be that this is the one at Gortavea and that Victor Love is who inherits and then has enough money to buy the land. Unfortunately, as the extract below shows, George is still being shown as a Farmer at Gortavea in 1881 in one of the directories, though this could well be out of date.

In this item from 1885 both Victor Loves are listed as Rated Occupiers rather than Freeholders, implying rented land again.

Which Victor Love is which is still a mystery, as both David and Victor Love are still living, unmarried by the look of it, on Creaghcor in 1901, when Victor and Victor Moorhead are living at Gortavea. Below are some of the references to Victor. Incidentally the Northern Whig was a largely Unionist and Presbyterian paper, though earlier were supportive of Catholic emancipation.

Here is Victor Love part of a meeting about forcing the Landlords to sell the land:

He is listed, later on in this article, as one of the delegates objecting to Home Rule.

Here he is a delegate at the national Ireland Assembly of Presbyterians.

Another edition of the Northern Whig has Victor Love presiding at a meeting with Abercorn or his representatives at Magheramason.

Below he is seen attending a meeting in Derry, about the agricultural depression.

Setting up a new Burial Ground

There are also multiple reports of meetings of the Strabane Guardians, who manage the Workhouse there and Victor Love is one of the Guardians. There is no proof that this is all the same Victor Love, but it seems quite likely. The ads in the clips are amusing.

This Victor Love marries Mary Moorhead in 1867 and their son Victor Moorhead Love is born in 1885. He, in turn, marries Eliza Dill Mitchell in 1913 and Ruth’s dad, George Victor is born in 1921. Incidently, when searching through family histories, using a wife’s family name as a second name for a son is often a sign that some form of money or inheritance is connected to the marriage and birth. That knowledge might connect to the inheritance or buying of some of the farm lands.

Ruth’s dad grew up on the farm, which was a dairy farm at that point and would have had to help around the farm as well as going to school, as is the case with most farming families. The roads around the farm had no hard surface and he told her that he went to school in bare feet. From an early age he would have known that he was expected to carry on the family farm when he became an adult.

That brings me to a convenient point to pause and move across to Donegal, where Ruth’s mother’s family were living. There are plenty of Loves there too, but we’ll leave them. Before I end here, I will just mention that I also found Loves in Strabane, but generally they were ones who had converted to Catholicism. Coincidentally they were usually poorer and less likely to read and write. The differences between Strabane and its surrounding areas still exist today.

The Donegal Connection

Ruth’s mum was born in Donegal, after partition, the daughter of Jane Bredin McArthur and the John Knox McCombe mentioned earlier. The McArthur’s lived in the townland of Carrownamaddy, Burt west of Derry. The McCombes lived in nearby Carrowreagh, Burt.

Jane Bredin McArthur was the oldest daughter of Joseph and Eliza Jane.

Inconveniently for them, perhaps, the McCombe’s moved across from the other side of the Foyle, around Artigarvan near Strabane, sometime around 1903, not too long before partition. Some members of the extended family stayed around Artagarvan.

The McArthur’s were long time residents of Donegal and under MacArthur or Macartur or similar variations can probably be traced back to the sixth century BCE. It is believed they converted to Protestantism around the time of King James the first. There are certainly records of wills in the early eighteenth century. At least one strand of the family still lives and farms the same farm.

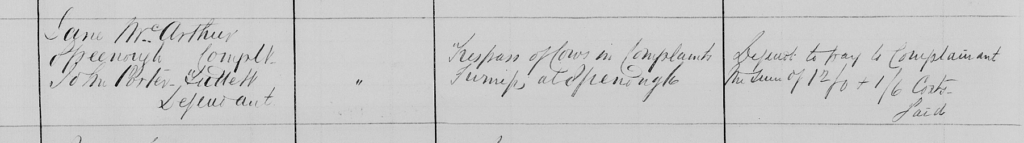

I am only going to pick a couple of highlights out of the long McArthur history. In the early 1800’s William McArthur married Jane Bredin and they had six children. Sadly, William fell from his horse and died in 1854, leaving Jane to look after the farm and raise the children. This she did with vigour. Below is her taking someone to court for trespass.

She did this several times. Below is her, in 1858, renting land and subletting it on one of at least two Townlands where she is doing so. Incidentally I guess that the Bredan entry at the top of the sheet is a relation. The figure of 64 in the fourth column is the acreage and the next three columns are valuations. Jane was controlling over 174 acres in total. In Donegal, Lord Templemore is the equivalent of Abercorn we saw in Tyrone. Templemore is an ancient name for Derry and the peerage belongs to the Chichester family, originally from Devon, who have held a variety of titles since around 1600. Like most farms, patrimony rules in succesion in what are called the Irish Peerages. Several Peerages are still named after Southern Irish places. The current incumbent of the Templemore title has seven titles in all, including Marquess of Donegal. What stuff and nonsense.

Jane Bredin/McArthur definitely enters my pantheon of powerful women, especially in the traditional farming environment where patrimony is so strong.

It is worth mentioning the Cole family of Legnaduff and the Mason’s of Castruse here as well. The reason will become clear later.

These three families are all protestant farming families, who consider themselves part of Ulster, as well as Ireland and the UK. When partition arrives, the border is not fully decided for several years and in 1925 a Border Commision sits to hear evidence from interested parties. It has already been decided that the six counties of current Northern Ireland will separate, but the details of the border are up for some discussion. The families living near the border can be seen making representations to this commission. Some are pointing out that their farm sits on both sides. Some are highlighting that most of their produce is sold on the other side of the border, for instance in what is then called Londonderry. Some are pleading for the border to move, so that their farm is on the other side. Children may go to school on the other side of the border as well. Below are some examples of this.

Below is a later family member doing the same.

In 1927 Mary Evelyn McCombe married John Foster Cole. The following year Jane Bredin McArthur married John Knox McCombe. In 1929 Jane gave birth to Yvonne, then Dorothy Elizabeth in 1931 (known as Betty and also Ruth’s mum), then in 1933 to Margaret. Within the same year as Margaret’s birth, John Knox McCombe dies. Mary and John Cole also have three children, then Mary dies (perhaps in in 1937). Following these unfortunate events, Jane Bredin and John Foster Cole get together and they have three more children. Then John F Cole dies and Jane Bredin is left on her own, with all the children. Sadly, in the genealogy search site I have been using, I can find little detail of any of this. The gap between the youngest McCombe and the eldest Cole children is filled by the second world war, less effective record keeping and frosty relations between Ireland and the UK.

Sometime after Samuel Scott (a name etched on my brain) Cole is born, his father John dies and Jane Bredin decamps from Donegal to the other side of the border. Ruth’s mum and her two sisters are around 20 by this time, so getting ready to move on in the world. There are stories about how much or little Jane Bredin is supported by families in bringing up all the children. She seems to have lived in a reasonably large house, though in the middle of a Catholic area. The younger children are sent to good schools, paid for by the Masonic Lodge, and go on into further education. Joyce marries James Mason, of the family who were talking to the Boundary commission, and they settle in Donegal. Dorothy (Betty) meets George Victor Love, is impressed by his dancing and the safety of relatively well off Protestant farmers. They marry and live at Foyleside. George Victor is in the volunteer reserve during the Second World War and roams the hills along the border on exercises. He may even have met my dad. When his dad dies He sells the prized dairy herd and turns the farm to arable crops. Ruth and her two sisters are born and then Victor Love, who is still at the farm today.

This history has seen a country divided, but families surviving and crossing that divide. Amongst the families I have covered there are those that can trace lineage back forever on the island of Ireland. There are families who have been in Ireland for a very long time but whose origins are clearly elsewhere. There are also those whose Irish lineage is much more recent, having only arrived at the end of the nineteenth century. As I have researched, I have noticed significant numbers with my own surname (Scott), who, as lowland clan’s people, may well have their origins in the Plantations or even the expulsion of the Border Reivers to the ‘wastes’ of Ireland. The history of names and directions of movement is unsure. All these families are of a complex lineage though. No-one should simplify their background too much. The families are loyal to their family and farm, perhaps in equal measure. Countries and borders come second to those. They are relatively well off, often with domestic and farm help. They can read and write and can often do things like play the piano. They lead lives that mix hard work and leisure and they work to protect that. Below is Ruth’s dad in the paper for playing Badminton.

Like many of us, the social circle is relatively narrow. The names there are all ones we now know from this family history, or ones that belong to other protestant farming families in the same area. For cricket fans, George Victor’s doubles partner’s grandson, Boyd and his brother David are two more tall strong Ulster farming offspring who played cricket for both Ireland and England.

As well as badminton, Victor loved a game of football and also racing round on a motorbike, neither of which probably helped with his eventual arthritis. Below he can be seen as President of the local football club.

Just to finish off the lineage, Ruth moved over to Lancashire and then to Yorkshire and had a daughter, Jessie. When Ruth and I got together, Jessie took one look at me and immediately decamped to the other side of the world, where she still lives, north of Auckland, with Rikki and Ruby and Grayson. Travel is built in.

The themes of these stories have been the complexity of people’s origins, the amount of travel that has always been part of many people’s lives and the importance to the world, of people who just get on with life and work. I have only traced parts of the origins of three people, with a few little side tracks on the way, yet the tale has been all over the place. I fully believe that any attempt to define people by where they are from, where their families came from, what their religion or beliefs are or what their sexuality is, has pernicious dangers. I hope you have enjoyed the stories and any new twists on history that they have brought you.