In the stories that I wrote, leading up to this one I have been moving forward from a particular person whose name I already knew and piecing together the information and checking the stories I think I know against what is available. In both cases the first person was a woman. I did go back a bit, but that always proves more difficult, especially with common names. In this one I am again starting from a woman, Jacky, but this time she is alive and well and is the mother of my daughters. Another fixed point on that investigation is Jacky’s dad’s mum, as she largely brought him and his sisters up on her own and Jacky’s dad was fond of stories and claims about his origins. Beyond that I am always in a quandary. If I follow the male line back it is often easier but loses a growing amount of the story each time I do so. There is also the problem of the variable quality of records. Thankfully the Catholic church has always been better at record keeping than the Anglican church and includes mothers names and origins more often. What I have chosen to do is to try to highlight points of interest on as many sides as I can make sense of. Jacky’s family might at first appear to be one that has stayed in the same area for generations. But research highlights and individual or even a whole tribe of such a family suddenly moves somewhere else. There are also clarifications or confirmations of little twists to the stories that families tell themselves.

In this episode we come across the Yorkshire Pennines, where families have been weaving wool for many centuries. By the end of the 17th century the system of ‘putting out’ was dominant. A merchant provided capital and used this power control the whole process. They bought the wool, contracted out the processing of the wool and then the making of the cloth. This control enabled them to have the geographical areas they dealt with specialise in different types of cloth. In turn they were able to mechanise parts of the process and still control the whole. Prepare to meet any number of strange job titles.

To be consistent, I won’t go into lengthy personal biography here. Once again I’ll try to give a flavour of the times as well as adding to the stories of some of the people we met earlier.

As the textile industry automated, so people who could make, service and mend machinery became important, and the availability of these skills led to other engineering industries setting up. Engineers make up part of this story too. As usual transport links are also important, but also things like water provision. These areas have been fairly densely populated for a long time and so infrastructure has always been important and there are stories here that relate directly to that.

Once again, we see people moving about both locally but also further afield. This time we bring southern Ireland into the picture, which, strangely, leads us round to Wales again. The trip to Ireland touches colonialism and the terrible events of the Irish Famine.

Ireland 1800-1911

The person we are tracing back here is called various versions of Nelly (Ellen) Evans. A glance at the name would not lead you to suspect Ireland as her origin, nor would Catholicism be your first guess as to religion, but she was born in Portrushen near Baltinglass, County Wicklow. All the places we are dealing with are on the border between Wicklow, Kildare and Carlow.

Ireland in the late 18th century and till long after Nelly left it, was run by the British. At first it was a dominion, but in 1800 it was incorporated in the Union, nearly a hundred years after the same happened with Scotland. Nellie’s grandparents may well have been born before that union. Irish nationalism was still disorganised and centred around a range of disparate problems. The land was mainly owned by Anglo Irish, who were either not Irish at all or were Irish who were members of the Anglican Church of Ireland. There was no Catholic emancipation until 1829, around the time Nellie’s father was born. Even then national schools were set up but teaching was only in English, Gaelic speakers were disadvantaged.

Where the Irish could get access to land it was under a tithe (proportion of produce) system, which was also largely under control of the Anglo Irish. That meant that the owners could withdraw access or raise prices(tithes) at will. In one of the other stories there was mention of the Napoleonic Wars, which led to a boom in some areas of the economy, but you may remember that these were followed by the Corn Laws that meant that there was pressure to produce cereals to feed England, so Land Owners started squeezing tenants and controlling production and crops to provide exports. This squeezing was especially common and strong in Ireland. In 1830 this led to outbreaks of violence in the same rural areas where there had been resistance to the Union. These areas centred around the richest farming lands surrounding Dublin, of which Wicklow is a key one.

The large net export of grain from Ireland was at the expense of local food supplies and there were repeated famines. During the 1840’s, when Nellie’s mum was born, there was the Great Famine, that lead to widespread starvation and death and the mass exodus of Irish to America and elsewhere. The Government, including local politicians, who were mainly English speaking Anglos, dealt with the situation abominably. The worse situations were on the west coast rather than the area we are dealing with, but the effect was felt everywhere. The situation was recognised all over the world for the disaster it was. Even the Choctaw Nation in America contributed to welfare funds, piling even more shame on the British government.

There were some improvements in tenant rights from just before Nellie was born through to the early 1900’s, but the early part of her life was dominated by the rise of Home Rule parties in the community and then in parliament. This would all lead to uprisings and eventual independence for the South, but by then Nellie was long gone.

So where do Nellie’s family fit into this mess of tensions? The answer is that they cross the social divide. Nellie’s father was an Anglo, either a British soldier from Wales or a descendent of one. It is no coincidence that there are a lot of Welsh names around Wicklow at that time. There are witnesses at several marriages, including Francis and Kate’s, and also Christenings, who are called Morgan and Byrne. Though Byrne is Irish it is the Anglo-Irish version of the name. Both these names are well represented in the burial ground near Portushen. There don’t appear to be census records until 1891, but in these records, there are Evans’ who are watchmakers or gunsmiths, so are in that middle ground between the poor and the well-off. I suspect this is where Nellie’s family belonged. People came as soldiers and often settled down and stayed. Depending on their rank, they either became part of the ruling classes or merged in with the local people to some extent.

Portrushen is a townland (a small subdivision of a parish or other land area often around 200 acres)). It is east of Rathvilly, south of Kiltegan and southeast of Baltinglass. The picture below is the old graveyard between Portrushen and Kiltegan. Portrushen is also not far north of Clonmore. Leighlinbridge, where it appears Nellie’s mother was born, is slightly further away to the southwest of Baltinglass. All these places are possibilities from the records.

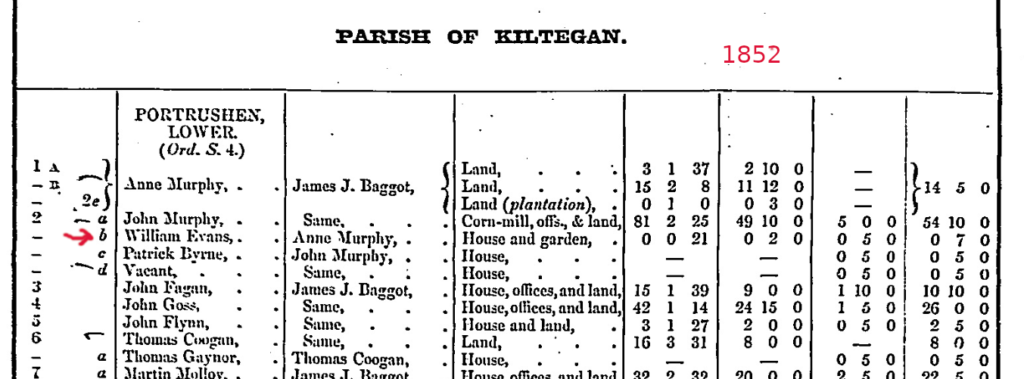

There is very little else at Portrushen, but there must have been some houses before the ones that are visible now, as a William Evans, who may or may not have been Francis’ father, rented a house and garden (see below)

At the time that Ellen Evans was born, Humewood Castle was being built not far away, so there will have been farms and other landownerships where people worked. As an example of scale, the castle is built in over 400 acres of land.

Ellen was born in 1877 to Francis Evans and Kath McCardle who were married in 1863, There is some doubt about when Francis was born (1822,1828,1834) and who to, but one possibility is him being born to William Evans and Mary Kenny, who were married in Rathvilly in 1831. They all lived in Portsrushen by then. Another possibility is that he was born in Wales. There is a Francis Evans who is registered to vote at a house on Church Lane in Baltinglass East in 1885 (see below).

Kath Evans is living in Baltinglass East, as a widow, in the 1901 Census and there is a Francis Evans down as being born in 1834 and dying in 1889. These all seem to tie together. As I could’t find a Francis Evans born in Ireland in 1834, that adds to the hint that he may have come from Wales. There are several possibilities in Cardiganshire and an intriguing one is a Francis who was born in New Quay, Aberaeron, a harbour port opposite Wicklow. His mother was the widow of a ships master, of independent means, but with a lot of children and living in what was previously the White Hart at White Street. Francis disappears after the 1841 census, but by 1851 he may well have moved on elsewhere. His mother is still living in the same place, with only one daughter remaining, in 1871. Because of the doubts over origin, it is not possible to say whether Francis was Catholic or simply converted for the wedding.

Kath McCardle was born in 1844 to Pat McCardle and Mary Molloy. Pat was born in 1819 in Leighlinbridge to Edmond McCardle and Brigid Murphy. Kath’s origin seems much more solidly Irish.

The first child born to Francis and Kath was Mary born in 1864 who dies in 1871, William was born in 1865 and may die in 1877, Michael in 1868 who dies in 1872, James in 1870, Catharine 1873 who marries Luke Hanrahan in 1896 and is living, without record of her husband, with her mother in 1901 in Baltinglass. Mary Teresa born in 1875, Ellen was born in 1876. Abb(E)y also appears to be born in 1876 and dies in 1890, She may have been from a different family, as she is not baptised. Frances was born in 1878 and maybe marries Matthew Murphy in 1900. There may be another child (Thomas) born in 1880 with the mother down as Cath McCarrel.

In 1911 younger Kate (Catharine) and Luke are back together and have elder Kate living with them in Winetavern Street, Merchant’s Quay, Dublin. Elder Catherine dies in 1912 the death is registered in Baltinglass.

What happens to Nellie after she is born is a mystery, as far as the records go. I tried tracing her in various ways, but none led to a more convincing trace. Even the circumstances round her marriage to James Rooks are in doubt, but I guess we better look at him and his origins before we come to that.

A circle round the Pennines 1720-1911

Nellie Rooks was married to James Rooks and lived in Todmorden when Jacky’s dad Percy was born. James had been born in Oldham in 1872 and was described in the Census as an Engine Fitter. His brother was also born in Oldham and was also a Fitter. His dad was also James and was born in 1840 in Oldham and was a Mechanic or Fitter. Elder James’ dad was called William and in the 1861 Census he was described as a Mechanic. You might detect a pattern here. Is it any surprise that Percy went on to become an Engineer?

Where William Rooks broke the mould was that he was born back in 1817 over the other side of the Pennines in Cleckheaton. His father was called John as was his father and his father before him. The latter John Rooks may have been born in either 1721 or 1730 to either George Rooks or Squire Rookes respectively.

The reference to Squire Rookes is interesting as there are two ancient Manor houses in this area, Bowling Hall and Royds Hall, both going back to the Doomsday book. Royds Hall was at one time owned by the Rookes family, who had tenanted it from 1330, but were granted ownership by Henry VIII for help with the dissolution of the monasteries. The last of the line to live in the hall ended up in Debtors Prison in 1785. The hall was later visited by Humphrey Davy. Whether there is any relationship between the Rookes and the Rooks is unclear.

What is clear from the baptisms of the Rooks is that they are Non-conformists and it seems likely that this continues through to the James that marries Nellie and becomes father to Percy. I suspect Percy was the first Catholic Rooks.

What the Yorkshire Rooks’ did as jobs is not clear but going that far back the jobs are likely to have changed. What is clear is that they are all moving around in the area between Huddersfield, Cleckheaton and Bradford. Those of you who have watched the TV series Gentleman Jack, may have a fair picture of the life, though that was set a short hop to the west. Contemporary accounts paint a grim picture of uncontrolled coal and ore mining and processing in a mix of open and underground mines, with multiple slag heaps and all this intermingled with sheep and ancient strip farming and cloth manufacture.

The Northeast 1892-1921

James Rooks disappears after the 1891 Census in Oldham. In 1911 he and Eleanor (Nellie) are living in Todmorden.

Fanny Maria Rooks can be found as born in 1901/2 in York. Percy can be found as born in Darlington in 1905/6 and Margaret in Halifax in 1909/10. In all three cases the mother’s former name is given as Evans, which ties in. I can’t find a record of a marriage until 1904 in Newcastle on Tyne.

Whatever went on in the gap to 1911, there they are in Todmorden as a family. Percy and his sisters go to school through the First World War. By the time of the 1921 Census there is another child, Frank, Percy is an apprentice Engineer at ‘John Pickles Sewmills Engineer’, Eldest daughter Frances is living there with her new husband John Law and James has disappeared from the picture. There are family tales of James being kicked out for drinking and a possible body in the canal, but none of that can be substantiated from the records. He seems to just disappear again.

In the 1921 Census we get some of our first typical Yorkshire job titles; Clothing Fustain Machinist; Letter Out Fustian Mother; Clothiery Tacker Ready Made. Even the company names are of interest; Fustain Clothiers Cowither Motor; Hallingwell & Midgley Wholesale Clothiers; R B Brown & Sons Wholesale Clothiers.

As with all these digitised records, unless someone is born, dies, or gets married, there is little else from 1921 till the 1939 register at the beginning of the Second World War. Percy told tales of walking miles to go to dances and then walking miles back afterwards. At one point he also apparently walked to London, working on farms for food and board. He also apparently played football for Halifax Town and claimed he had earned more in expenses than from his his pay from his day job. If he was an apprentice when he played, that might make sense. At any rate he used the experience later in life to be a respected coach of local amateur teams in Linthwaite. By 1939 he appears to be in Lodgings just on the edge of Huddersfield town centre and is presumably working at David Brown Gears, where he worked until he retired. We’ll leave him there while we look back at Jenny Gartery, who he later marries.

Huddersfield and Bradford 1850-1947

We might as well start the section on Jenny Gartery with 1939 Register and interesting job titles. Below is the entry for 88 Upper Clough:

Apart from Lena on domestic duties and Betty, who is at school, I suspect that the only job title not to do with textiles is Jenny’s. I know that she worked at Standard Fireworks, over the hill in Crosland Moor, at one point and that on at least one occasion the snow was so deep that she had to walk along the tops of the dry stone walls to get there. Packing is the sort of job you do at a Fireworks factory. Once again in this directory we see it giving secret hints toward the future, with Jenny and Doreen having their future names as well as their present ones.

In an earlier iteration of this part of the tale, I decided not to follow the Gartery line, as that has been well explored by the family. However my own connections with the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, and my love of following female lines that are often ignored, got me thinking again and as I had a short subscription to a geneology site, I have rooted out more. First though, I can’t resist my usual gloat about the origins of solid northern families though, as Willy Gartery’s dad was born in Salisbury, Wiltshire, as seen below.

I must be fair and say that neither Gartery or Rooks lines ever made anything of me being a southerner. This background in the south still surprised because I had always contrasted my own globe trotting forebears with Linthwaite folk who stayed in the same place for generations. My own daughters went to the same junior school as their mother, who went to the same school as her mother, who may have gone to the same school as her mother, or at least one nearby. My Linthwaite grandchildren went to the same school too.

Unlike the 1939 register shown earlier the census record for 1911 gives a lot more clues to follow. First is that by now elder William Gartery, Sarah Jane and family are by now living in Slaithwaite, on or near the Manchester Road. There are ten in the same house.

The next clues come from the place of birth and ages. The older offspring were born in West Bretton. This lends weight to the idea that elder William and Sarah Jane met in West Bretton. William is on the 1851 census in Wiltshire, with parents John and Anne. The location is described as ‘Extra Parochial’, which means outside any parish. I suspect this means that they are on a big estate. This in turn adds weight to the idea that elder William moved up to work on the Bretton Hall estate, as a movement from one rural area to another seems usually to mean connections in the owning families. As usual there is some doubt about it all as another search made me stumble over more Gartery’s in the Barnsley area, such as Edwin Gartery, who was also born down in Wiltshire, so there may have been a family exodus. Further investigation shows that this William was a plough boy, aged 10, on the Clarendon Park Estate, in the 1861 Census, and a brick yard labourer at age 20 in 1871. Clarendon Park was built by Peter Bathurst, MP for Salisbury, whose family have strong slave owning connections.

The woman William Senior married was Sarah Jane Gibson. At first I thought her mother was described in the 1861 Census as a widowed Toll Gate Keeper in West Bretton. My later investigation made me think that I may have been mistaken and Sara Jane just working for that woman as a servant. It is not easy to make sense of the records, so there is some doubt about the details. Today you can see the Toll Gate referenced in the name of a recently rebuilt farm on the edge of West Bretton leading out to Midgley. There were two toll bars at some time, one there and one at Midgley itself. The Toll Road ran from Barnsley to Grange Moor. Local humour would probably see why people would want to leave Barnsley, but not, perhaps, why you would want to arrive in Grange Moor, which is renowned for having its own unpleasant weather systems. The widowed toll gate keeper married George Robertshaw, who also died and, by the time William was living with them in 1881, she was living in Brick Row, West Bretton. This may be the row of brick cottages on the left as you enter the village from the Huddersfield direction.

Back to Sarah Jane Gibson. She was in fact born somewhere around Darton, near Barnsley in 1854. Her parents were Timothy Gibson (born 1817/1821 in what is described as Tipsy-in-Notton, Royston, Barnsley) and Mary Truelove (born1821 in Darton, Barnsley). His parents were Jonathan (B1791) and Jane(B1786). Mary Truelove’s parents were called John and Sarah, so Sarah Jane was named after her grandma.

All the names featured back in Sarah Jane’s line seem to come from the area between Barnsley and Grange Moor, roughly following the line of that Toll Road.

As hinted at by the 1911 Census, the Gartery family moved from West Bretton at some time and were either in Kexbrough or Darton, or both when the younger children were born. This is Sarah Jane’s family area and, if you look again at the 1911 Census, you can see that they have brought someone from nearby Mapplewell with them over to Slaithwaite.

Back to Huddersfield and the 20th Century

In fact, Jenny’s mum, Lena Smith was born in Bradford, but had been in Linthwaite at least since the 1891 census, first at Linthwaite Hall (there are around 30 houses/households with this address in this census) and then at Hellawell buildings on Manchester Road and after that at Spa View, also on Manchester Road. From these records we can add Hank Winder, Weaver Woollen and Wool Sorter to our list of job titles.

It is worth putting in a picture of Linthwaite (Linfit) Hall, even though they may not have lived in this building.

Lena was born just before they moved from Bradford and her mother’s name was Martha Hannah Birkby. I know that, like me, Jacky was amused by the name Uriah and its Dickensian connections, so we’ll trace that back.

Uriah married Martha Hanna Birkby from Cleckheaton and this and a job title have allowed me to decide which Uriah is the right one. This one comes from what was known as North Bierley, though he was born in nearby Bowling. The house was on Heaton Hill and this is a picture of those houses.

Here is the 1881 Census.

It looks like Uriah’s dad was John Smith and his dad was Samuel Smith, who was a coal miner, born in 1809. When John Smith started work they were living in Green End, Bradford.

Uriah Smith married Martha Hannah Birkby (b1864) in 1886 and Lena was their oldest child, born in 1888. By 1891 they had moved to Linthwaite and all the later children were born there. All of them are likely to have gone to Clough School, which had been built by the nearby Methodist church.

The Smith family are living at Spa View in 1911, when Lena marries William Gartery. By 1921 the couple are living at 2 High House in Linthwaite and Jenny is the second oldest of 5 children (b1914).

By 1939 the family have moved to 88 Upper Clough, which is just further up the Clough than the bottom of High House. The Register for then was at the head of this section. At sometime during the war, Jenny went to work at David Brown Gears. As far as I understand it her job was to set gauges accurately so that they could be used to check that jobs met design tolerances. The gear factory made gears of all sorts and all sizes, some so big that the drainpipes had to be taken off the buildings so that the vehicle transporting them could get them down between the buildings to leave the factory. You will not be surprised that a lot of the gears that they were making at this time were for tanks and other military vehicles.

I worked in the offices at the same factory in the 1970’s and there were strict rules and classes of workers even then. There were separate canteens and car parks for shop floor, office and supervisory, senior staff and then directors and senior management. To make a phone call, you had to get permission from your supervisor then go to Personnel to get a chit, then go out into the yard and hand the chit in to the Gatehouse, where you could queue next to the public phone box until it was your turn. There will not have been many car parks during or immediately after the war, but the regime will have been even stricter.

I am guessing that Jenny will have been one of few women fitting into the shop floor group, so they will have received plenty of attention, whether wanted or not. At some point Percy became a firebrand socialist shop floor convener. He was apparently such a nuisance that he was promoted to senior staff level as an Inspector. The Percy I knew always had confidence, charm and chat, so will have been popular.

In 1944 Jenny and Percy married and rented a small (now Grade 2 listed) cottage at Daisy Green, yet further up the Clough. There were gas lights, no electricity and an outside toilet that was emptied by the council. In 1950 Jackalyn was born and then Janet a couple of years later. At some point they briefly moved to a council house in Slaithwaite, but then restored normality by moving to 90 Upper Clough, next door to Jenny’s family.

I’ll leave this strand of the story there and move back down to London for a bit of personal social history ad then catch up with Jacky and Janet later.

Kensal Rise 1950-59

When we left London in an earlier part of the story, I was on the way and we were living in Keslake Road, Kensal Rise. The house was a large, good looking, mid terraced one and was definitely stretching things financially. It is shown below:

There were two other couples in the house too, renting rooms from us. As far as I can tell, dad was working as a maintenance carpenter, at Ascot Hot Water Heaters in Neasden at the time. I suspect that, as he did most of his life, he was working six and a half days a week, with a half day on Saturday. Mum was working in the NHS as a qualified Midwife, but it is unlikely that her wage would be taken into account for mortgage calculations.

The details of the house purchase are below:

I have estimated that dad’s annual income was probably around one third of the mortgage on the property and that they paid around a quarter year’s income as deposit. So, while they were stretching things to the limit, this was a house that could be purchased by ordinary working people. A few years later relative values of these houses would drop as prejudice encouraged the residents to move because the Windrush Generation were moving in to flats in the bigger houses up the street. I certainly accused my parents of that being one motive for us moving when I was 8 and Rob 6. I remember the phrase ‘they bring house values down’ being used in partial justification. They don’t bring house values down, the people who move do.

Over the years I kept an eye on the house and area, because I always liked these big houses, a fantasy I have grown out of. At some point ‘gentrification’ started happening. The result is a microcosm of our stupid housing market. Below are the sale details for a similar house across the road that has been renovated and re-designed.

Let’s be generous and say that a skilled tradesperson, working a lot of overtime, could earn £50,000 per year. One quarter of that income would be £12,500. The equivalent ten percent deposit on £1.9m would be £190,000, somewhat beyond the means of that skilled first time buyer. The ninety percent mortgage would be £1.71m, which is a bit over 34 times their annual income.

Rant over, but it is simply immoral that we let a basic human need, like housing operate, in a market like that and that unearned profits from homes are not taxed sensibly. Changing that is the only thing that will alter this stupidity.

I am uncertain of most memories from this house, but I know that Mum went back to work after I was born and that I was dropped off at a local nursery. Only after Rob was born did mum give up nursing, I think, and for a while worked in a local shop. There was also a bakers shop on the main road at the top of ours and fresh loaves used to come down a chute into the shop, straight into a machine that sliced them. I was impressed. In the opposite direction to the main shops, there was a corner shop just down the road and Queens Park further down again, though my main memory of the park was being taken down there with new football boots and a heavy football that I/we had been given for Christmas. Not my idea of fun I’m afraid.

I went to school aged four, but that first year was more about playing than studying I suspect. This is the school as it is now.

There was the nursery class in a portacabin, with a separate small playground, an Infants section with another playground and pre-fab huts. The junior playground was on the side in the picture. There must have been a lot of pupils. I was told that after the first day I would not go with my mum and another boy and his big sister collected me from our house each day.

Once we started learning to read and write, I was in trouble. Being so strongly left-handed I wrote backwards and over the years my writing went through various transformations as I tried to find a way to write forwards, often rubbing out or smudging what I had just written as I moved on. Add to this the swap from our first writing style to a style with elaborate cursive letters, that is even harder left-handed and nearly slicing my hand off on Boxing Day when I was six, I didn’t take to school at first. On the plus side, it was in the Junior playground that I first discovered the joys of being a fast and agile runner and the sense of achievement and acceptance this gave me stuck with me throughout life.

A highlight of this time was being taught to make an Origami dinosaur head by a frustrated teacher, because we were chatterboxes. Thus, was born a lifetime habit of paper folding. Another highlight was coming across two people who could draw well and being so fascinated by the skill that I copied and repeatedly practised until I had that skill too. As the combination of smog induced asthma and regular visits to the hospital because of the hand accident meant that I was often out of school for the next couple of years, drawing and making things out of pipe cleaners, plasticine and anything else I could get my hands on became far more important to me than schoolwork. I was always in trouble because my notebooks had far more drawings in them than notes.

In the relatively short time that we were in Kensal Rise, Reg and Jean moved in, uncle Gilly and auntie Margaret moved out. Then Reg and Jean moved out too. A young woman moved into the upstairs front room then locked herself in and tried to commit suicide, resulting in dad shinning up a ladder and breaking in through the window and the poor woman being committed. At some point Idris Morgan came to stay as well and was still there when we moved house. We did take him with us though and, after a quick peep round the new house he said he’d spotted a nice pub on the way in and would see us later.

After a stressful visit to the doctor about a stuck foreskin, I developed an imaginary friend called Plepper, who at first just kept me company on painful toilet visits, but later even ventured out of the house. Aunty Vi returned from Australia bringing me a toy kangaroo and Rob a toy koala. She got into the habit of taking me around London and to the library in Willesden. On one occasion I left Plepper in the Library and Vi nearly got us off the bus to get him.

A London bus of the time. Apparently, I used to spend most of my time opening and closing the windows. Much later, when I was at Art School, I dropped my heavy art folder at the top of the steps of one of these and it bounce all the way down and off the back platform of the bus, surprising a few people on the pavement.

Dad changed jobs and started roaming all over the country building exhibitions and even going to Brussels to build the British Pavilion at Expo. I suspect part of the reason for the job change was the extra money needed because of people moving out of the house. His long absences obviously caused confusion in my small mind as at one time I thought that he had to duck to walk through doors. I must have been thinking of someone at least 35cm taller. Talking of doors, I developed another party piece to go with fast running, which was shinning up the door frames to hang from the top.

One November dad managed to drop the lighter into the fireworks. After we had all listened to the noise from the safety of the house, we set out on a walk round all the local shops that were open, trying to find some replacements. Luckily for dad, I had befriended Dad (not mine) and Miff and their adopted son David next door, so we were able to combine our meagre pickings with theirs and have a reasonable show. I think Dad and Miff took pity on me for having parents who let me fall through plate glass doors, spoiled the fireworks and made me climb up door frames, so, when they moved down to Somerset, Dad came up in his car and collected me for a holiday down there, where I saw bread being baked in a wood burning oven, rode ponies bareback, saw cottage cheese being made, wandered down dark lanes as bats flew overhead and generally had a wholly unforgettable time. Dad’s possession of a car and, later, Vi’s acquisition of the same, were noticeable events. Personal vehicles were few and far between and we didn’t have one.

Incidentally, also during this time, dad’s lifestyle without schedule caught up with him and he collapsed on a station platform in Dorset with a burst duodenal ulcer (when your mum was a nurse you remember these things). They removed half of his stomach and duodenum so we had to go down there to visit him while he was convalescing. Together with our trips up to Lancashire and Cumberland, I am beginning to think that mum and dad moved out to Colindale in the hope of a quieter life.

Barrow and Detroit 1950-1954

My impression that half of Barrow had moved down to London makes me suspect that the shipbuilding town was suddenly seeming a less attractive place to its residents. Perhaps that explains why Uncle Fred and Aunty Vera, together with their daughter Cheryl (born in 1950) and Vera’s mum and dad, all suddenly upped sticks and went to live in Detroit. The city grew hugely towards the end of the nineteen forties, was the hub of the newly developing interstate highway network and was building housing in suburbs, where the increasingly large automobil factories were also being sited. They arrived, got jobs (Fred in the GM factory and Vera’s dad as a butcher), found somewhere to live, bought fridges (fairly rare in the UK still), bought cars ( a huge Dodge for Fred and a Chrysler), had a second daughter (Marilyn), visited Uncle Bert in Canada and watched the Coronation on TV (also rare up until that year in the UK).

I remember two contemporary film clips of the end of a factory shift from this time, that I saw many years later. The one in the USA had people flooding out of the factory, mostly in cars, some on motorbikes, some walking, but hardly any on bicycles. The one in the UK had virtually all the workers walking out of the gates, reasonable numbers on bicycles, a couple on motorbikes and perhaps one senior manager in a car. People in the UK had often met US forces during the war and had probably had two main reactions to them. One camp thought they were brash and boastful and resented their presence. The other group was understandably mesmerised by the relative wealth they represented. They might even be tempted to try some of that lifestyle for themselves.

In the case of the Scotts and Lows the shine didn’t last long for some. First Grandma Low decided she missed home and returned, then Fred decided he was homesick too, so the Scotts followed. Finally, Grandpa Low had to throw in the towel and follow the rest back. Fred would often wonder what came over him to return, but it was obvious that he felt happier overall in Barrow. Apart from a short spell in Shaw, near Oldham, for third daughter Karen’s schooling, Barrow was where they stayed for the rest of their lives. Cheryl still remembers those cars though.

London 1959-1970

I suspect not many people around in the nineteen fifties who could remember Kensal Rise when it was fields. It was largely Edwardian and to this day is connected to central London by the overground railways, rather than the underground. When we moved out to Colindale there were still plenty of people who could say that they remembered the fields. It was one of a number of newer suburbs built along the A5 London to Holyhead Road, known in London as the Edgware Road. Incidentally the two houses were roughly the same cost at the time of the swap, but now you could get the second house for a bit less than a third of the older one. Mind you that is still a ridiculous price compared to current incomes.

Everything was different out here. There were places to roam, along rivers, round reservoirs, through parks and along off-road footpaths. There was an outdoor swimming pool where I learnt to swim in temperatures below 10c. The local school was in large grounds (with bomb shelters of course), had a vegetable garden and playing fields with a football pitch with goals and Long and High jumping pits. The kids’ accents were less broad cockney. I was put in a lower streamed class, the kids asked me if I knew what a knob was (a door handle I thought), then we went out to the field at playtime, raced from one corner to the other and once again my speed gave me a form of acceptance. Rob and I contentedly became latch-key kids, he became a high jumper, I became a sprinter and long jumper. Rob fitted into the top stream class, after a while. I didn’t really gel when I was moved up to the top stream, so my friends were always in the classes below. Neither of us took to football, much to dad’s disappointment. I developed another party-trick, when a friend with callipers on his legs because of polio showed me how he could walk on his hands instead. A playing field and some sun are great for practising and as a pair we were never beaten in a wheelbarrow race. It is getting a bit hard to do a hand-stand now, but I can make a go of it. By the way never talk to me about problems with vaccinations unless you have seen the problems caused by not having them.

After a while, time came to take the Eleven Plus exam to see if I was suitable for Grammar School, and I wasn’t, so off I went to Edgware Secondary Modern. Three years later Rob was more than suitable and went to Orange Hill Grammar School, which was the school where mum now worked in the school labs. Orange Hill was a bit of a classy Grammar School, with some celebrities sending their kids there, but there were some similarities in the schools. Both were on boundaries between working class, largely Christian neighbourhoods and better off areas with large Jewish populations. As a result both schools had some Jewish teachers and there were separate Jewish assemblies. Rob and I were both subject to a wider range of influences than was common in a lot of schools. Edgware School actually allowed (in my case persuaded) us to take the more readily accepted ‘O’ level exams rather than the relatively new CSE exams normal to secondary schools. Orange Hill had an assumption that one possibility was to go on to Oxford University, which even a lot of Grammar Schools did not emphasise. Random bits of luck can have a long-term effect on your life choices and possibilities. Rob was one of a few in the wider family who went to Grammar school, an opportunity only mum had had in the previous generation. I was not held back significantly by not going, but I suspect that not taking ‘O’ levels would have limited my choices a bit more.

I suspect it was the influence of my Jewish friends that allowed me to choose to go to Art School instead of continuing into the sixth form. Not only that but to apply to one of the ‘posh’ Art Schools. I was only recently reminded of this by someone who grew up in the same area, who said that you had to be seriously good to get in there. I am not sure that is true, but I was the only one of my contemporaries to do so. It didn’t stop me wondering what I was doing there, as the reality of the Art World became clear. I soon turned tail and went to college to study Maths, Statistics, Economics and Computing at ‘A’ level, enabled by those ‘O’ levels. Entertainingly, the head of the Art School implied that they’d probably never had a student with such Maths skills before.

We are approaching 1970 and the end of this section, so it is worth catching up with what the rest of the family were doing before we move on again. After we moved to Colindale, Dad decided to learn to drive and finally managed at the third attempt with the aid of tranquilisers. Not many people who knew him would believe that he suffered from tension so badly. Mum followed him shortly, passed first time but never really took to driving and was glad to pass the mantle to me when I passed and then Rob later.

Dad’s first and second cars above. The first became mum’s. I suspect that dad and his mechanic friend had a little bet on when they persuaded me to lift the front end of the blue one up so they could put it on blocks.

Dad kept swapping jobs, including a period working for an infamous John Bloom at Rolls Razers, where they actually sold washing machines at this time. Unlike my cousin’s husband who got out in time, dad was then left with outstanding wages when the company went bust. On the plus side he did get to see a Park Lane penthouse and other very big houses, as he did jobs for the directors as well as the work at the factory. He kept returning to Ascots as an old faithful.

Gilly and Margaret moved out to the suburbs before us and Blanche and family followed later. Slowly everyone left London, as its appeal faded. I went off to University in Lancaster. Rob would then go off to Israel for a year before he went to Oxford and mum took the opportunity to try to escape us by moving dad up to Blackpool to run a hotel sized boarding house. Once again, I’ll leave it there to catch up with Jacky’s story.

Linthwaite 1950 – 1970

The ‘clough’ of Upper Clough is a narrow side valley to the Colne valley. There is a reservoir at the top, built by excavating the top of a ridge where one side led down to Meltham and the other to the bottom of the Colne Valley at Titanic Mill. Incidentally the mill was nicknamed after the Titanic Liner as it was opened in the same year as the ship launched. In the picture above, the Clough runs down from right to left. On the right you can just see the roofs of Daisy Green, where Jacky was born, to the left of the tiled roof. The trees just above the second dry-stone wall are at the top of the gardens for the row of houses where Jacky and Janet grew up. The Manchester Road is way down in the bottom at the left hand side.

There were more mills part way down the Clough, on a small side road called Waingate. Because the clough is steep sided and the sides were filled in using the rubble dug out for the reservoir, the houses on the upper part were simply given 100m long strips of garden running up the otherwise practically unusable hillside behind them. The borders were drawn on paper and have often been questioned ever since, usually without too much falling out. Before the houses were built culverts or land drains were built under the rubble from the excavations and the rights to water from these belonged to the dyeworks in the valley. Despite the steepness they have been fairly extensively cultivated over the years. Jacky’s grandad had a heated greenhouse part way up the slope, with a small well. A family called Bower had a large yard between the terrace where Jacky lived and Myrtle Grove further down the road. There was a large shed and here many of the older local men used to sit and smoke, until one day they set it alight. In the same way the local women used to pop into each other’s houses. The women tended to called each other by their surnames and even used their husbands name. So Mrs Harry Senior lived a few doors down from Jacky. This could even be shortened to Mrs Harry, but that usage was reduced when there were four houses in a row with husbands called William. Four women called Mrs Willy was too much to bear. Before she was Mrs Harry Senior she was Betty Maxwell and lived further up the Clough. Similarly the Bowers moved up and down the road, as they married and changed names. The names became less formal in later years. It was that sort of place. As well as being a Sales Rep for Thornton and Ross in the valley bottom and thus being one of the first to get a car, Harry Senior was the Mayor of Colne Valley for a while.

There was a kind of social order to the whole Clough. The Methodist built Infant and Junior School was about 200m up from Manchester Road, then a further 100m up was the Methodist Church. The Methodist Church was a dominant force and the movers and shakers within it were proud of their roles. There was certain amount of social cohesion and its opposite, discrimination. Many of the organisers within the church lived in slightly larger houses nearby. After church on a Sunday they would often walk up the Clough and take the air round the reservoir at the top, dressed in their, suitably modest, finery. These family’s were slightly above other locals and they often remain so today. As the daughters of a socialist firebrand and also Catholics, Jacky and Janet were even called heathens by other children. In the way of these things other people’s perception of you shapes your own self perception. Of course the rest of their local relatives were still Methodists and Harry Senior lived next door but one, so they can’t have been all bad?

Jacky’s dad Percy was also hard to pigeon hole and ignore. As Works Convenor at David Brown Gears and then a senior manager, later as a respected local football coach, he commanded a bit of respect. he became and honorary life member of both the local Working Men’s Club and the Liberal Club.

There was also a pattern of jobs that tied in with the Gartery household and people used to come out of their houses to go to the same workplaces, either towards Slaithwaite or back towards town. The Colne valley is a very ancient textile area and the whole valley is covered with lanes, pack horse trails and footpaths and ginnels for people to travel around. You can trace routes from all over the valley to the churches in Marsden or Almondury. There are routes from the wool and spinning areas at the top of the hills down to the mills in the bottom. As you walk the paths, you can imagine people treading them in clogs on their way to work. Later the buses followed similar routes to take people to and from work.

Our children went to school with the sons and daughters of sons and daughters of the same people who were around the Colne Valley for most of the twentieth century at least.

There was a long row of stone terraced houses, shown at the right in the picture above called Myrtle Grove, then, four sets of terraces of three of four houses. The lowest houses had decent sized cellars and three bedrooms, the next set had half cellars and three bedrooms, the next two bedrooms and no cellar and the top set two smaller bedrooms and stairs up the middle instead of the side.

When Jacky was young, mills were still running, and coal was being burned all along the valley. Houses were black and grass was grey. Along the Manchester Road at the bottom of the valley Trolley buses ran, with the wires they need for their electricity trailing along the road above them. There was no M62, so the Manchester Road really was just that. A very busy and polluted thoroughfare. Incidentally the Manchester Road in the valley was the second major Manchester Road. The first was built by ‘Blind Jack’ of Knaresborough and ran along at the top of the Clough. When Jacky was young, the stretch across to Crosland Hill was known as Sandy Lane and wasn’t tarmacked. It turns out that Blind Jack had his own patented road surface mix, before Tarmac was invented and that was the ‘Sandy’ surface that had been there since the end of the eighteenth century.

If you come down what is now Holt Head Road, you come to a T junction and opposite is the dusty track above. I think that was originally part of the Manchester Road.

Because Jacky was bright and at the older end of her cohort year, she was put up a year when she went to high school. This sounds flattering but means that you are the youngest in your year by far. Incidentally this area of the country was ahead of most, as the school Jacky and her sister attended was a comprehensive, theoretically making it easy to make up for mistakes in streaming. Jacky managed to survive through school despite the mismatch of ages and in 1968, at the age of 17 went to Lancaster University to study French. This was a four-year course with a year working in France. Remember that Jacky was still a year younger than her contemporaries, so that will have made the year harder.

When Jacky returned to Lancaster for her final year, I was in my second year. Though the relationship was not always smooth, it eventually resulted in Jassa and Kara, so we’ll leave the story there.