When people are taught to paint landscapes, they will often be told to make things further away tend towards lighter and bluer. Unfortunately sometimes people tend see this as a rule, rather than a painting trick to emulate the effects of distance and atmosphere on colour saturation. There are lots of similar guidelines that can become a hindrance if taken too literally.

If you read about the painter John Constable, you will almost certainly come across the tale of him and Joshua Reynolds, where constable puts a violin on the grass to demonstrate that they are not the same colour, after Reynolds objected to the colours in Constable’s paintings.

When photography came along it changed the way we see things and motion photography even allowed us to see how things actually move for the first time. At the same time photography took away visual art’s dominant role in capturing a likeness for posterity. This in turn allowed artists to investigate other roles for their art. Increasing awareness of science, particularly relating to colour and vision, also gave artists new ideas about how to do their job. There have been many debates in art history about how to do things and some of these relate to vision and how we see and remember the world around us.

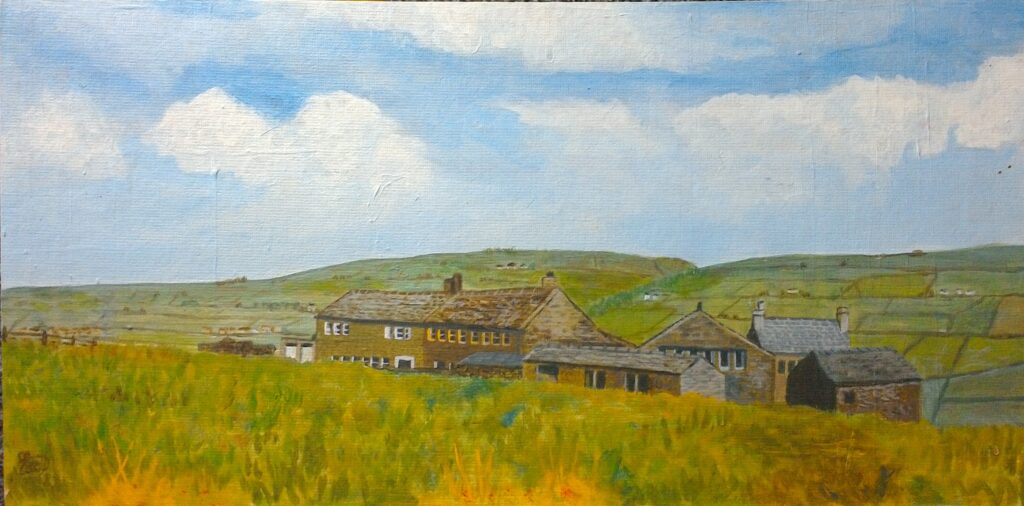

If you ever stand in front of a wide open landscape and enjoy looking at it, a temptation is to take a photograph. I’d be pretty surprised if you weren’t often disappointed with the result. All the magnificent detail and sweep of light you see will have been largely lost. Even a sophisticated camera has limitations of focus, whereas we can focus near and far repeatedly and rapidly without really noticing that we are doing it. Most of the time it doesn’t even make us dizzy. The vision we have in our head is then a combination of what we have seen and felt, with special emphasis on all the things we have been most interested in.

The next element of perception that is important to highlight separately is memory. While our memories are unreliable, they are still ours. We are capable of holding a lot of detail about a scene, as well as host of related generalisations and also feelings. I know of painters who repeat the same scene repeatedly from memory. Each version is different but also alike. Whether intensionally or not, each painting will often be recognisably by the same person.

That last bit about repeating a scene painting also relates to our ability to produce and recognise schematics of things. Every child does it very quickly in their development and even animals are able to do it. Those Captcha tests that have popped up over the last few years, designed to demonstrate your humanity, would be within the capability of a pigeon or crow, as long as they had been taught to associate the schematic with food.

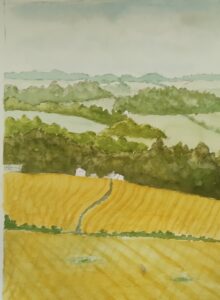

In the pencil sketch below the are no colour hints about what we are seeing and little difference in tone between near and far. In fact the mast at Emley Moor has more definition than it might have in a photograph, representing what we would see by changing our focus temporarily. Within the picture there are plenty of hints about scale and perspective from the lines and objects. The effect is strong enough for us to recognise that the field in the distance is just a different shape, rather than badly drawn.

So if you do want to paint a scene, reasonably realistically, for someone, based on a photograph, don’t be afraid to paint it as they might see or remember it. Equally don’t be afraid to represent what you want to represent without being a slave to the myth of realism.