In a previous post, on AI, I wrote that we still don’t really understand quite how we think. A comment by Ruth while looking at an animated weather map suddenly brought together for me a whole mass of observations and ideas that I thought might be worth putting down on Cloud paper.

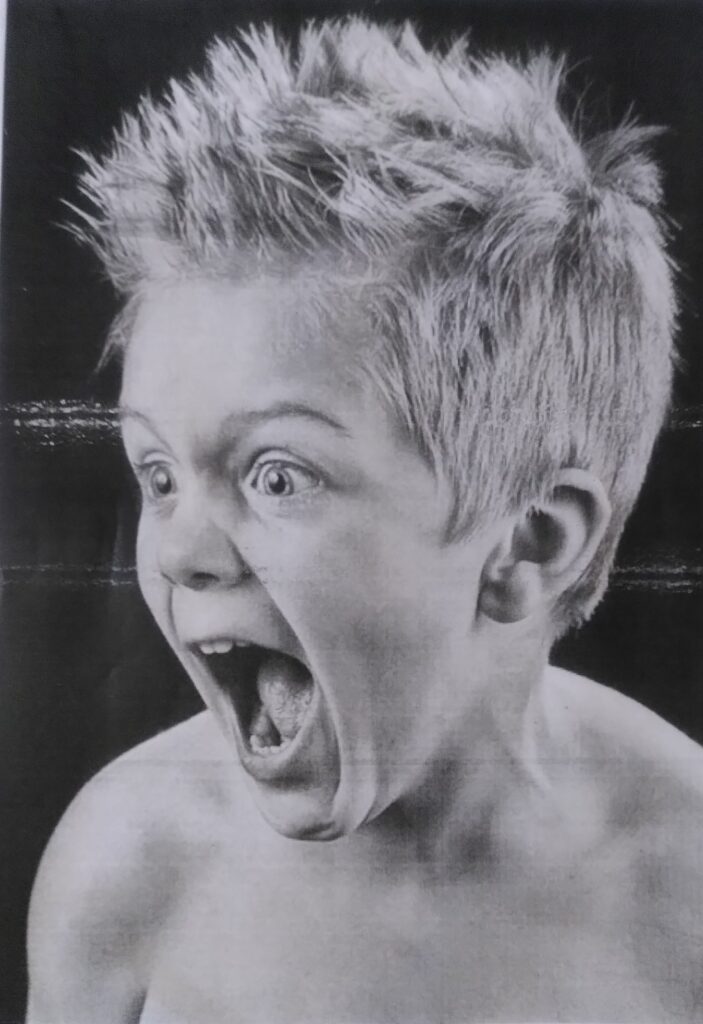

So how do we get those sudden moments of apparent clarity? We know that it is to do with our constant monitoring and building of synapses, but we don’t really know what is going on.

Let’s get back to some basics. I used the word Thinking in the title, but for most of us that means just the tiny percentage of brain work that we are somehow also aware of as we do it. There is a whole complex set of process going on behind that. Those processes also do not end where our brain is either, they are affected by and have effects on our bodies. Recent research has unpicked some of the complexities of how birds manoeuvre , through foliage for instance, and it has highlighted just how complex and integrated all the information processing is.

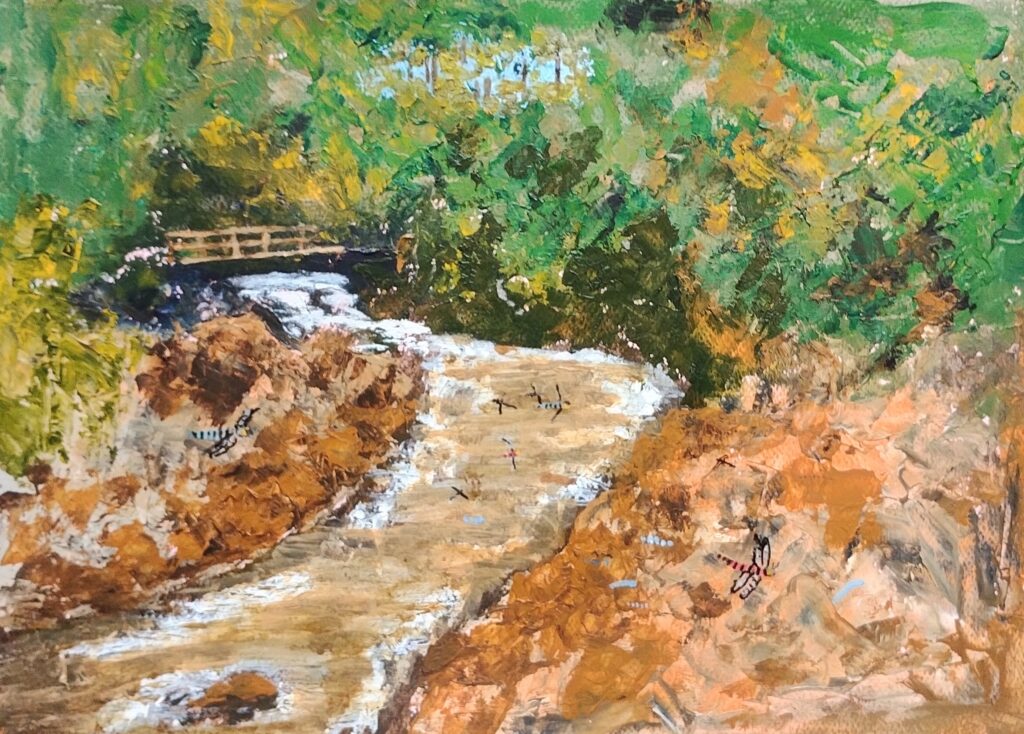

Of course it doesn’t end at the periphery of our bodies either. Hive minds and the communication signals that pass between trees have entered popular imagination in recent years. On a personal level, I have been astonished many times by the speed of my reactions to outside stimuli over the years (and a few times by their failure too). While I have no chance of controlling the fastest reactions, my brain and body are also instantly busy categorising, analysing and planning further actions. Amazingly it is also observing all this happen. In windy conditions, a huge branch nearly came down on me in the New Forest one year. I escaped injury, more by luck than reaction times, but it is still in my brain as some sort of learned experience. Not only that but I can now abstract from it and realise that the tree would have picked up signals from the falling and landing branch and my clumsy evasive dance would have been registered as well by both the tree and other life forms in the vicinity, whose own reactions would have effects and so on. It wasn’t just Ruth and I who were on alert that day.

Thinking about all that, we must remember that the complexity may mean that everything cannot be processed and analysed perfectly. Our brains have to sacrifice some detail for more useful gains in learning. Different living things and individuals inevitably have different abilities to process and use their experiences. I have always had difficulty holding onto names and numbers but that hasn’t stopped me from being fairly good at things, such as maths, that involve numbers for instance. Others will outshine me in some areas but fall behind in others. Everything is a compromise in one direction or another.

The same is true of AI and AI has another layer of difficulty to deal with, in that it often needs to find effective ways to communicate what it has found. Communicating involves reaching an agreed sense of meaning and importance with those you are communicating with and that is hard.

This takes us back to our maps. What prompted the discussion Ruth and I had, was zooming in and out on the map and the choices that the app made on what to include on the map at the different levels. Not surprisingly it failed to realise the relative importance of different pieces of information to us. IT, with or without AI, has always had this problem. In earlier days the compromise decisions were made by humans but they are now frequently made by code. Human decision makers are far from perfect but they often have an instinctive understanding of other human understanding. Despite all its advances and amazing powers, code still has trouble realising what is obvious to us.

To be continued…..